“A work of art”, so the saying goes, “is never finished, merely abandoned.”

This assertion rings true in many artistic spheres, to the extent that I’ve seen variations attributed to people as diverse as Leonardo da Vinci and W.H.Auden.

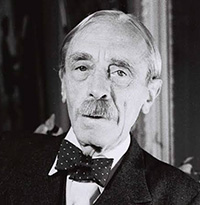

The site ‘Quote Investigator’ suggests that it actually originated in a 1933 essay by the poet Paul Valéry:

The site ‘Quote Investigator’ suggests that it actually originated in a 1933 essay by the poet Paul Valéry:

Aux yeux de ces amateurs d’inquiétude et de perfection, un ouvrage n’est jamais achevé, – mot qui pour eux n’a aucun sens, – mais abandonné …

and they offer this approximate translation:

In the eyes of those who anxiously seek perfection, a work is never truly completed—a word that for them has no sense—but abandoned …

My knowledge of French idiom falls short of telling me how significant Valéry’s use of the word ‘amateur’ is, though. Is he saying that it’s the professionals who really know when a work is complete?

~

Anyway, the same original core assertion is sometime used when speaking of software: that it’s never finished, only abandoned.

It’s rare that any programmer deems his code to be complete and bug-free, which is why Donald Knuth got such attention and respect when he offered cheques to anyone finding bugs in his TeX typesetting system (released initially in the late 70s, and still widely-used today). The value of the cheques was not large… they started at $2.56, which is 2^8 cents, but the value would double each year as long as errors were still found. That takes some confidence!

He was building on the model he’d employed earlier for his books, most notably his epic work, The Art of Computer Programming. Any errors found would be corrected in the next edition. It’s a very good way to get diligent proofreaders.

Being Donald Knuth does give you some advantages when employing such a scheme, though, which others might want to consider before trying it themselves: first, there are likely to be very few errors to begin with. And second, actually receiving one of these cheques became a badge of honour, to the extent that many recipients framed them and put them on the wall, rather than actually cashing them!

For the rest of us, though, there’s that old distinction between hardware and software:

Hardware eventually fails. Software eventually works.

~

I was thinking of all this after coming across a short but pleasing article by Jose Gilgado: The Beauty of Finished Software. He gives the example of WordStar 4, which, for younger readers, was released in the early 80s. It came before WordPerfect, which came before Microsoft Word. Older readers like me can still remember some of the keystrokes. Anyway, the author George R.R. Martin, who apparently wrote the books on which Game of Thrones is based, still uses it.

Excerpt from the article:

Why would someone use such an old piece of software to write over 5,000 pages? I love how he puts it:

“It does everything I want a word processing program to do and it doesn’t do anything else. I don’t want any help. I hate some of these modern systems where you type up a lowercase letter and it becomes a capital. I don’t want a capital, if I’d wanted a capital, I would have typed the capital.”

— George R.R. Martin

This program embodies the concept of finished software — a software you can use forever with no unneeded changes.

Finished software is software that’s not expected to change, and that’s a feature! You can rely on it to do some real work.

Once you get used to the software, once the software works for you, you don’t need to learn anything new; the interface will exactly be the same, and all your files will stay relevant. No migrations, no new payments, no new changes.

I’m not sure that WordStar was ever ‘finished’ , in the sense that version 4 was followed by several later versions, but these were the days when you bought software in a box that you put on a shelf after installing it from the included floppies. You didn’t expect it to receive any further updates over-the-air. It had to be good enough to fulfill its purpose at the time of release, and do so for a considerable period.

Publishing an update was an expensive process back then, and we often think that the ease which we can do so now is a sign of progress. I wonder…

Do read the rest of the post.

It’s rather pleasing to discover, investigating it now, that the verse comes from

It’s rather pleasing to discover, investigating it now, that the verse comes from

Recent Comments