Are there any stores that you like to go into, but rather hope that you won’t be spotted there by anybody you know, because it would be a bit embarrassing? One of these, for me, is Edinburgh Woollen Mills, which seems to have, as its target market, old-age pensioners with little sense of taste or fashion. On the other hand, when I have crept in there over the last few decades wearing my false moustache and dark glasses, I’ve always found their plain woollen sweaters (and a few of their other less-tartaned items) to be excellent value, well-fitting and very hard wearing (which is good, because I then don’t need to visit too often and risk being spotted).

Well, I had a similar desire to conceal my location yesterday, when I was invited onto Radio 5 Live at very short notice to talk about the passing of Sir Clive Sinclair, his influence on the UK’s computer industry, and the importance of having a culture of invention. That was what the text said, anyway, but in fact they ran out of time and so, I think, slotted me in to the last few mins of the show, just to be polite, and join in whatever discussion was ongoing. With the result that we said nothing about Sinclair, almost nothing about computing, and in fact discussed time travel and whether butterflies could fart. (Don’t ask.) It wasn’t the high point of my broadcasting career. The good news is that I suspect there are even fewer of my acquaintances who listen to Radio 5 Live than who shop at Edinburgh Woollen Mills.

I never met Clive Sinclair, though he had a big influence on my life, having produced, in 1981, the first computer that our family could actually own. The BBC’s enjoyable 2009 dramatisation ‘Micro Men’ portrayed him as a bit of a comedic monster, as I remember, and I’m not sure how fair a representation that is. The programme is now available on YouTube, and I must watch it again, because it does depict several people I do know, and generally does them quite well, so perhaps it was accurate. Recommended viewing for all British geeks of a certain age, anyway.

I never met Clive Sinclair, though he had a big influence on my life, having produced, in 1981, the first computer that our family could actually own. The BBC’s enjoyable 2009 dramatisation ‘Micro Men’ portrayed him as a bit of a comedic monster, as I remember, and I’m not sure how fair a representation that is. The programme is now available on YouTube, and I must watch it again, because it does depict several people I do know, and generally does them quite well, so perhaps it was accurate. Recommended viewing for all British geeks of a certain age, anyway.

But it is sad, in a way, that Sir Clive is often remembered for the C5 — his low-slung electric tricycle — which was a dismal market failure in 1985, and the butt of much humour, including from me (though as a techy teenager I would secretly have loved one!)

What did impress me, though, as I was making notes for the interview, was the relentless rate at which Sinclair released products:

- 1977 – The Wrist Calculator and the MK14 kit computer

- 1980 – The ZX80 – the first affordable home computer in the UK

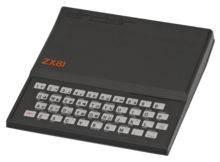

- 1981 – The ZX81 – a much better version

- 1982 – The ZX Spectrum – the UK’s best-selling microcomputer

- 1983 – The C5 electric trike, and a pocket television! (Which of course, back then, still had to use a CRT.) Also the Microdrive storage system, using tape-based cartridges which could store a whopping 100KB!

- 1984 – The Sinclair QL

- 1987 – The Cambridge Z88 – a portable computer with a full-sized keyboard, which ran for ages on four AA batteries. I have one on the desk beside me here.

That’s quite a list for a small company over one decade!

The failure of the C5 basically killed Sinclair Research, and the Sinclair brand was sold to Amstrad in 1986, which is why the Z88 was released under the Cambridge Computer name.

The failure of the C5 basically killed Sinclair Research, and the Sinclair brand was sold to Amstrad in 1986, which is why the Z88 was released under the Cambridge Computer name.

This failure was notable, though, because it followed the great successes of the previous years, which had made Sinclair a household name, and, by deploying affordable, programmable machines into vast numbers of British homes, played a big part in kick-starting the UK’s technology industry. It certainly kick-started my own hobby and eventual career in computing, which is also a good thing for the nation, because otherwise I might have tried to go into broadcasting.

So I would like, if I may, to propose an epitaph for Sir Clive Sinclair:

It is better to have invented and failed, than to never have invented at all.