I was once out for a walk with a friend who had also been a major investor in one of my startups. I bought her a cup of coffee and she said, “Oh, let me pay for that!” and I responded with, “Don’t worry, I owe you about a million quid anyway”. She laughed, but I know she remembered it.

And so did I, because afterwards I realised I was wrong. I had fallen into a common trap: an assumption that those who receive money should necessarily always be grateful and subservient to those who provide it. In one sense, those who are on the receiving end are naturally inclined to feel that way, because without it, our business, our grand plan, our pet idea, wouldn’t survive. In the short term, we need them more than they need us. But (except in very rare circumstances) it’s a deal, not a donation. Investors in startup companies are not just doing it out of the goodness of their hearts; you are giving them something in return; they are, in a very real sense, paying for your services, in the hope that everybody will make a profit out of it (and probably them much more than you). What I should have added, to my investor friend, is something along the lines of, “I owe you about a million quid, but I guess you owe me and several of my friends many years of our lives, so perhaps we’re quits.”

This is true of employment, too. For those of us fortunate enough to be in the Western tech world in a period of high employment, we’re making the same deal: you’re giving me money, I’m giving you a certain fraction of my life. This is not a master-slave relationship, it’s a barter relationship, and if either side doesn’t like the deal, they can go elsewhere or (increasingly) set up in business on their own. I appreciate that this is an historical, geographical, and industrial anomaly, or at least novelty, so please don’t send me emails about the Tolpuddle Martyrs! (Been there, seen the tree.) But it’s the world many of us are fortunate enough to live in now. The them-versus-us tribalism of management and workers in the industrial revolution, or in the 1970s and 80s, is no more helpful in the 21st-century tech business, or the 21st-century gig economy, than it is in 21st-century Facebook-exaggerated politics.

Thinking about this reminds me of a conversation in a Seattle cafe with my late friend Martin King, when he was asserting that there was no reason companies should not have the same ethics as, and be as nice as, individual people. (He was referring to their dealings with other companies, more than employee relations.) I applauded his intentions (and tried to follow them myself to a significant degree).

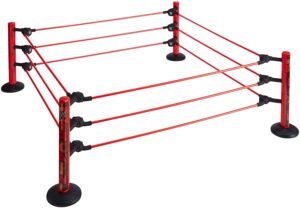

However, I pointed out, there was a fundamental difference between business and personal relations: business is inherently competitive. It’s more like a sport than a social function, and you need to understand the rules from the word go. Imagine if you entered what you thought was a garden party, and it turned out you were in rugby match, or a boxing ring. Human interactions work if everybody inside, say, the boxing ring, knows the rules and plays according to them, but they are different from the rules of normal social engagement.

The relationship between a company and its employees, of course, is not, one hopes, competitive in the same way, but it is still a business deal, a game played according to certain rules. This is why the recent attempt by the founders of Basecamp to clarify the rules of their game was, I think, both admirable and controversial: their rules seem very sensible to me, but some people thought they were playing a different game (or wanted to) and so departed for another playing field. Sometimes, yes, the rules need changing. Sometimes they need clarifying. Sometimes they should have been clarified earlier. But sometimes you’re just on the wrong playing field!

So make sure you understand the rules of the game you’re playing. If you’re accepting money from an investor, remember that they’re doing it because they expect to get at least as much from you in return. If you’re earning easy money as a driver because you installed an Uber app (rather than having to apply for a traditional job with an employment contract), be aware of the nature of the relationship and don’t complain because you later decided you wanted something different. And if you should happen to wander into a boxing ring thinking it was tea at the vicar’s, don’t be surprised if what you get in your mouth isn’t a cucumber sandwich. This is a fault in your research and your expectations, and not necessarily in those of the person delivering the surprise!

Once you know which playing field you’re on, of course, you should then be a good sport to the best of your abilities! And so should companies.

Recent Comments