John’s excellent column in the Observer this weekend was a reminder to those of us who enjoy driving EVs that we shouldn’t feel too smug about our environmental impact.

Electric vehicles have a greater carbon footprint in their manufacturing process than fossil-burners, and it takes a while for the environmental benefits after you drive it off the forecourt to make up for this. In countries like the UK, where it’s relatively easy to get your electricity from renewable or nuclear sources, that’ll probably take about 6-12 months. In countries like the US where you’re probably getting a lot more of your ‘fuel’ from coal, it could take several years, and it’ll probably be the second or third owners of an EV who really have a more carbon-neutral vehicle!

In the intervening period, though, we can feel a little bit more virtuous because — and I do appreciate that any pro-EV points I make in this post might definitely be classified as self-justification! — at least we have moved a lot of pollution away from highly populated areas. (This is distinct from carbon footprint, which can happen anywhere and has a much greater area of impact.) When it comes to human health, though, we’re only starting to get to grips with, for example, the damaging effects of the tiny particulates emitted from exhaust pipes — Tim Smedley’s book Clearing the Air is an excellent explanation — and the key thing about them is that they don’t travel very far. You are more at risk in a cycle lane next to traffic than are the pedestrians a few meters away… especially if they walk on the further side of the pavement.

I’m often annoyed by people who sit stationary with the engine running, while waiting for their kids to come out of school or their spouse to come out of the supermarket… and then I have to remember that the poor things are in such primitive vehicles that they can’t even keep themselves warm in their cars without polluting the local area.

Long-lasting?

One thing we don’t know much about yet is the longer-term outlook for individual vehicles, because they just haven’t been around long enough. EVs are generally expected to outlive their internal combustion predecessors because they have far fewer moving parts, less vibration, less thermal stress, and so forth. Yes, the batteries will have a limited lifespan, but they can be replaced, and they don’t get thrown away: their consituent materials are much too valuable not to recycle.

What’s also sometimes not appreciated by the Jeremy-Clarkson-watching fraternity is that these aren’t like phone batteries where you have to replace the entire thing. Car batteries are made up of lots of cells packaged into modules, and individual modules or even cells can often be replaced when they start to fail. Yes, we all know rechargeable batteries do wear out… but they don’t die suddenly; their capacity just decreases over time (or more specifically, as they go through an increasing number of charging cycles, which usually corresponds to mileage).

When Nissan started producing the Leaf, they announced all sorts of plans for how they would recycle and reuse the batteries when they were no longer useful in the cars. In fact, though, few of these plans have really come into play yet, because cars and batteries are lasting far longer than expected.

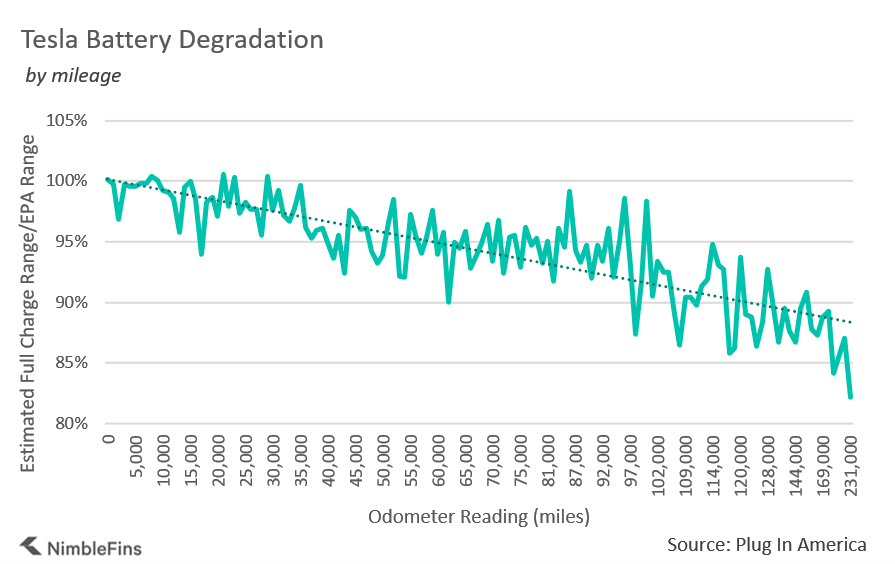

Part of the reason battery life has never really worried me from a practical or financial viewpoint is that battery range has also been increasing. This page describes a study of Tesla Model S batteries (the Model S having been around longer than most), and includes a nice graph showing the battery degradation against mileage:

Now, I happily drove my previous EV for 5 years, which had a range of about 70 miles. My current car has a range of around 300 miles. If it follows this trajectory, then after 20 years of my current 10,000 miles per year, it will still have a range of around 250 miles, which is plenty for almost anybody, and certainly for me!

Let’s talk about cobalt

The issues around the sometimes-worrying mining practices of the rarer elements involved in battery manufacture are well known, and a cause for concern. Cobalt, in particular, is a key component of current batteries and is mined almost exclusively in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Somewhere in the range of 15-20% of this is done by small-scale mines, often in hazardous working conditions, and some modest proportion of this is done by children.

Certain companies, like Tesla, claim to have eliminated these sources from their supply chain, though how much they can really have achieved this is uncertain. It’s partly for this reason that there is significant research going into creating cobalt-free batteries, but in the meantime, it is a situation which needs (and is getting) considerable attention.

It is, however, a situation for which we are all culpable, not just EV owners (though we EV owners take more of the blame). But you’re probably reading this on a device that includes a battery containing cobalt. And cobalt is used for many other processes too.

Something like 41% of cobalt production is for use in batteries. And roughly two-thirds of that – about 27% of the total – is for electric vehicles. (Sources here and here.) So the proportion of cobalt used by EVs is about the same as the combined use in carbide-tipped drills, paints, and cobalt-based catalysts (the vast bulk of which are used, in fact, for oil-refining!)

So we should treat with skepticism those headlines that suggest that there’s child labour in cobalt mines in the Congo because of EVs. Yes, some single-digit percentage of cobalt production does involve children, and yes, there’s more of it because of EVs. We EV owners need to acknowledge that, while also pointing out that EVs represent only a quarter of the cobalt use in the world. Anyone who owns a laptop, iPad or mobile phone, or drives or travels in fossil-fuel-based vehicles… even people who like blue paint — we all need to take responsibility.

And while admitting that our electric vehicles do not come guilt-free, I think we do need to remind that bloke in the pub that powering internal combustion engines has been known to have one or two negative aspects too! Conscience doth make cowards of us all. 🙂

Quentin – are you aware of particulate pollution:

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/03/car-tyres-produce-more-particle-pollution-than-exhausts-tests-show

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/feb/23/health-impact-tyre-particles-increasing-concern-air-pollution

can be worse for electric cars, like Teslas, since they’re heavier than ICE cars. In any case we should all be using electric bikes not electric cars whenever possible.

– Robert

Hi Robert – yes, and the higher torque of EVs can cause more tyre wear as well. On the other hand, EVs emit less brake dust (another cause of particulate pollution) because of regen braking… I’m not sure how these things balance out! But it’s a problem with all vehicles that use tyres – even bikes – to some degree. At least EVs stop emitting particulates when they stop moving, though! So perhaps they’re still more virtuous in densely populated areas.

For years I’ve been wanting an excuse to get an e-bike. My distance from town now is small enough that I should really just cycle, and just far enough and windy enough to make me usually take the car. It’s a case of balancing the decadence of replacing an ordinary bike with an electric one against the virtue of an e-bike vs a car… 🙂

Thanks very much to you and John Naughton for two thoughtful posts about EVs. But there are three significant issues with EVs – size, weight and energy efficiency that neither of your posts address – probably because they’re not being discussed at all. in all three areas EVs are much worse in than cars powered by internal combustion engines.

1. Size. Cars are getting bigger in general and EVs are bigger than cars powered by internal combustion engines – one reason is the characteristics of batteries you discuss above. But the space available to cars – especially in urban environments – is not. This makes congestion worse, makes parking worse, and reduces the space available to people making genuinely climate friendly travel choices by walking or cycling. This in turn stops people walking, cycling or wheeling. EVs increased size also makes it harder for drivers to see vulnerable road users like people (especially children) walking, cycling or wheeling. This leads to …

2. Weight. This is very serious for several reasons. EVs are heavier than cars powered by internal combustion engines. This makes EVs more unsafe in a collision as mass = force*acceleration. A pedestrian hit by an EV at 20mph will be more likely to be killed or suffer a serious injury than a pedestrian hit by a car powered by an internal combustion engine. Due to the Fourth Power Law – stress on roads increases in proportion to the fourth power of the axle load of the vehicle traveling on the road – EVs cause much more damage to roads than cars powered by internal combustion engines – increasing demands on constrained budgets for local councils – which sits uneasily with the tax breaks offered to owners of EVs. Finally much or our infrastructure is designed for lighter vehicles – a car park in New York collapsed recently partly due to the weight of larger vehicles parked in it. Expect more collapsing car parks in future.

3. Efficiency – however the electricity that’s used to power them is generated, cars are astonishingly inefficient – with 95% of the energy they consume being used to power the vehicle not the occupants – as EVs are heavier than cars powered by internal combustion engines then this effect is more extreme. As Helen Thompson points out in her book ‘Disorder’ much of 20th century geo-politics and much of geo-politics in the future has been and will be driven by access to energy. We need transportation to be much more energy efficient. (A recent study showed that bicycles are the most energy-efficient form of transportation of all animals). Cars in general also make extremely inefficient use of space (see above), they cause congestion on our roads which EVs exacerbate, and they spend 95% of their time parked – a cost to society which is subsidised by people who don’t have cars.

From my perspective the power source is a side issue to problems created by the UKs over reliance on the private motor vehicle.

Hi Richard – thanks for the above. Lots of good comments, though I have some suggestions in relation to some of them.

1) EVs aren’t necessarily bigger – in fact, they’re often smaller – than the petrol equivalents, because manufacturers have a lot more flexibility in their layout. You can create the same internal space with a smaller external space when you don’t have to stick an engine in front of the passengers. My first EV was noticeably smaller (and actually even lighter) than the diesel Golf it replaced but had the same space inside. And VW’s own replacement for the Golf, the ID3, is also marginally bigger inside while having almost identical external dimensions.

Now, it is the case that, because of the early-adopter prices, EVs have tended to be more expensive and so have targeted the luxury market, which means that they are, on average, bigger than most IC cars – and Teslas, in particular, are bigger because they’re also designed in America! But that’s not a requirement of the technology… in fact, the opposite is generally true.

2) You’re right about weight – EVs are generally heavier, and often much heavier. I don’t think this has any significant effect on pedestrian safety because if you’re being hit by a car, your survival will depend on many things more important than the speed at which you decelerate it (which would be the application of the F=ma equation) 🙂 Things like shape and crumple zones are much more important, and all of theses are much less important than the actual speed of the vehicle.

If you’re in another vehicle, though, the weight of vehicle that hit you would be more of a issue. Of course, if you’re actually in the EV… :-)

You’re quite right about the effect on road wear, though. The only thing that might mitigate that a bit is that EVs tend to have their load distributed much more evenly between front and back and so the actual per-axle weight may be less than the heavier axle on other vehicles, which will be the one that counts. But I may be splitting hairs there!

My hope, though, is that EV weight will come down as people get over their early-stage range anxiety and are willing to accept smaller batteries and shorter ranges. This will also be helped as battery energy-density increases, and as charging points become faster and more numerous.

3) No disagreement with your comments about cars being an inefficient way to transport people, but the extra weight of EVs is also offset by their greater efficiency in other areas. Even if you power them using fossil fuels — with electricity created using oil-fired power stations — the efficiency of those power stations is higher than the small combustion engines in cars and the gains are comparable to the effect of the weight difference. (Also EVs recoup fairly significant amounts of power through regenerative braking, which can’t be done on ICE vehicles.)

But of course, most EVs are not powered that way, they are powered by renewable sources in ways that ICE cars never can! Mine is currently charging from the solar panels on my roof and for much of the year most of my driving really is powered by sunshine I capture myself, though longer trips do mostly come from grid power, which I buy entirely from clean, renewable sources.

But I’m all in favour of eBikes and other alternatives to cars, and in smaller cars for local trips. I’m hoping I’ll be able to get a Microlino in the UK before too long!

Best, Quentin

Hi Quentin,

Anecdotally, my new bosses boss confirmed that car batteries can have a long life. His Tesla has done 100k miles and he claims the range is pretty much what it was when the car was new.