When I was young, somebody told me, “You should never borrow money for anything smaller than a house.” It was good advice, and ever since, I’ve disliked the idea of spending any money I haven’t yet earned. I drove old bangers, and fixed them myself, until I had the money to buy something better. I’ll only buy a new car now when I have enough money in the bank to pay for it. And I don’t use credit cards.

When I was young, somebody told me, “You should never borrow money for anything smaller than a house.” It was good advice, and ever since, I’ve disliked the idea of spending any money I haven’t yet earned. I drove old bangers, and fixed them myself, until I had the money to buy something better. I’ll only buy a new car now when I have enough money in the bank to pay for it. And I don’t use credit cards.

So I’ve always disliked the idea of graduating students starting their working lives with large amounts of debt, and when student loans first appeared in the UK, just as I was finishing my undergraduate course, I was opposed to them. Twenty years on, Oxford, Cambridge and a large number of other places are likely to be charging the full £9,000 tuition fee next year, and lots of people are up in arms about it, but I find myself feeling rather differently.

I was fortunate to have had a good education, and to have experienced both state comprehensive schools and a fee-paying private school. The teachers, in general, were good, intelligent and dedicated, in both. The students, the facilities, and everybody’s expectations, were rather different.

My parents, being teachers, would have struggled to afford a private education for me, but it was a high priority for them and I was fortunate to win a scholarship which allowed me to have a few more years of it than might otherwise have been possible. And what I really appreciated about life at the private school was that this was a place where learning wasn’t despised by the other kids, where everybody had worked towards at least a basic level of academic achievement to get here, and where everybody knew that daddy was paying a lot for the privilege. Not everybody felt that way, of course, but that was how it struck me. Yes, education should be a right for all, but there is also a large degree to which we value more that for which we have to pay more. Or, to be more precise, that for which we can choose to pay more.

One of the things my father found difficult when he returned from a couple of decades of teaching in Africa was to have students who didn’t really want to learn. He had never encountered that before, in a place where education was a privilege available only to a few…

Now, not having kids, I haven’t followed this recent debate closely, but this is how I try to keep things in perspective:

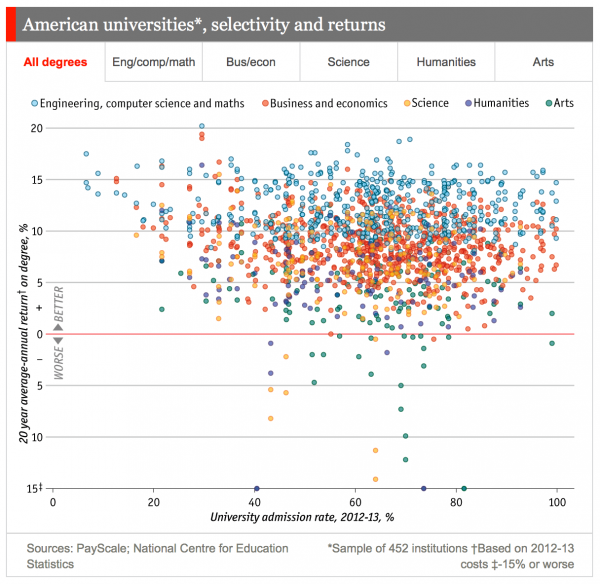

- If the top universities like Oxford and Cambridge do levy tuition fees of £9000, they will then be charging, per year, approximately what Stanford, Harvard and M.I.T charge per quarter.

- Most Oxbridge colleges have been running at a loss for some time – the money they have been getting from the government has long been insufficient to cover the per-student costs. There is already a heavy positive discrimination in favour of those from less-privileged backgrounds, and that will, if anything, increase.

- The repayment terms of these new fees are such that the average cost of your higher education, once you start earning, will be about the same as the average UK mobile phone bill.

Arguably, education is one of the few purchases more important than a house. So, perhaps, having to borrow for it is not such a great hardship. Even if you do have to give up your mobile phone in exchange.

The Guardian is running a piece under an attention-grabbing but rather irresponsible headline:

The Guardian is running a piece under an attention-grabbing but rather irresponsible headline:  When I was young, somebody told me, “You should never borrow money for anything smaller than a house.” It was good advice, and ever since, I’ve disliked the idea of spending any money I haven’t yet earned. I drove old bangers, and fixed them myself, until I had the money to buy something better. I’ll only buy a new car now when I have enough money in the bank to pay for it. And I don’t use credit cards.

When I was young, somebody told me, “You should never borrow money for anything smaller than a house.” It was good advice, and ever since, I’ve disliked the idea of spending any money I haven’t yet earned. I drove old bangers, and fixed them myself, until I had the money to buy something better. I’ll only buy a new car now when I have enough money in the bank to pay for it. And I don’t use credit cards.

Recent Comments