I was once out for a walk with a friend who had also been a major investor in one of my startups. I bought her a cup of coffee and she said, “Oh, let me pay for that!” and I responded with, “Don’t worry, I owe you about a million quid anyway”. She laughed, but I know she remembered it.

And so did I, because afterwards I realised I was wrong. I had fallen into a common trap: an assumption that those who receive money should necessarily always be grateful and subservient to those who provide it. In one sense, those who are on the receiving end are naturally inclined to feel that way, because without it, our business, our grand plan, our pet idea, wouldn’t survive. In the short term, we need them more than they need us. But (except in very rare circumstances) it’s a deal, not a donation. Investors in startup companies are not just doing it out of the goodness of their hearts; you are giving them something in return; they are, in a very real sense, paying for your services, in the hope that everybody will make a profit out of it (and probably them much more than you). What I should have added, to my investor friend, is something along the lines of, “I owe you about a million quid, but I guess you owe me and several of my friends many years of our lives, so perhaps we’re quits.”

This is true of employment, too. For those of us fortunate enough to be in the Western tech world in a period of high employment, we’re making the same deal: you’re giving me money, I’m giving you a certain fraction of my life. This is not a master-slave relationship, it’s a barter relationship, and if either side doesn’t like the deal, they can go elsewhere or (increasingly) set up in business on their own. I appreciate that this is an historical, geographical, and industrial anomaly, or at least novelty, so please don’t send me emails about the Tolpuddle Martyrs! (Been there, seen the tree.) But it’s the world many of us are fortunate enough to live in now. The them-versus-us tribalism of management and workers in the industrial revolution, or in the 1970s and 80s, is no more helpful in the 21st-century tech business, or the 21st-century gig economy, than it is in 21st-century Facebook-exaggerated politics.

Thinking about this reminds me of a conversation in a Seattle cafe with my late friend Martin King, when he was asserting that there was no reason companies should not have the same ethics as, and be as nice as, individual people. (He was referring to their dealings with other companies, more than employee relations.) I applauded his intentions (and tried to follow them myself to a significant degree).

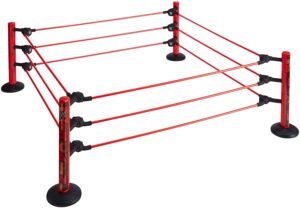

However, I pointed out, there was a fundamental difference between business and personal relations: business is inherently competitive. It’s more like a sport than a social function, and you need to understand the rules from the word go. Imagine if you entered what you thought was a garden party, and it turned out you were in rugby match, or a boxing ring. Human interactions work if everybody inside, say, the boxing ring, knows the rules and plays according to them, but they are different from the rules of normal social engagement.

The relationship between a company and its employees, of course, is not, one hopes, competitive in the same way, but it is still a business deal, a game played according to certain rules. This is why the recent attempt by the founders of Basecamp to clarify the rules of their game was, I think, both admirable and controversial: their rules seem very sensible to me, but some people thought they were playing a different game (or wanted to) and so departed for another playing field. Sometimes, yes, the rules need changing. Sometimes they need clarifying. Sometimes they should have been clarified earlier. But sometimes you’re just on the wrong playing field!

So make sure you understand the rules of the game you’re playing. If you’re accepting money from an investor, remember that they’re doing it because they expect to get at least as much from you in return. If you’re earning easy money as a driver because you installed an Uber app (rather than having to apply for a traditional job with an employment contract), be aware of the nature of the relationship and don’t complain because you later decided you wanted something different. And if you should happen to wander into a boxing ring thinking it was tea at the vicar’s, don’t be surprised if what you get in your mouth isn’t a cucumber sandwich. This is a fault in your research and your expectations, and not necessarily in those of the person delivering the surprise!

Once you know which playing field you’re on, of course, you should then be a good sport to the best of your abilities! And so should companies.

I think the challenge here is that many of the internet-business playing fields are designed for, and perhaps only really accommodate, white men of a certain type. If there are very few alternative playing fields available, and land is not available to build more, the keen players may wish to redesign some of the white men’s ones to better suit a wider selection of players… and perhaps some different games, in time. Some of us may choose not to play with others who bend the rules, or bribe the ref, or are particularly violent, or perhaps who are simply paid twice as much, but that can leave very little space to play in, in internet-business, to date.

My metaphor may be failing, here 🙂 but consider how you would feel if you found that the other players with you on your field were experiencing a totally different set of rules to you. You and they all signed up for tea, say, but the vicar is beating up the others behind the sofa, and it seems like you have not noticed but are just enjoying the cakes. That, I think, is the experience of too many in the tech industry.

Hee hee… I shall have to watch the vicar more closely…

Well, you may be right, though I would disagree with the suggestion that there are no new rules to be invented or different games to be played… especially in the tech industry! If you come up with a game that is fairer and more enjoyable for more people, then I think more people will want to play it.

I will, in the interests of diversity and equality, mention that on two out of the three local companies I can think of where your extended metaphor might possibly fit, the pugilistic vicars were women. 🙂 But yes, they were both white!

Indeed, pugilistic vicars come in many forms. It’s increasingly evident in some places that white women are indeed more problematic than one might think – perhaps because they have seen this technique work so well for the dominant demographic. Still, there are a lot more difficult white men still in lauded positions of power. In cambridge, some of the most difficult make a particular point, in public, of supporting diversity and inclusion…

I do hope more money and attention can be given to the new games; I suspect the usual way this happens is that they are just much less evident, and smaller, because money and attention follow, well, famous white male ‘tech thought leader’ bloggers, such as Fried and co…

That reminds me of the line in a song by the wonderful Katie Melua:

If a black man is racist, is it okay,

when the white man’s racism made him that way?

My first job was working for Martin King at Exbiblio. It was a fantastic place to work, in a big part due to the respect the leadership had for the employees. He set the bar high for my expectations of later employers.

Hi Spencer –

Yes, me too. The more years pass by, the more I realise how much I learned from Martin.

Q

“Understand the rules of the game you’re playing”

There’s more than a hint of the free marketeers’ niavety in that, where if employees obey and follows their orders they will be rewarded according to their deal with their fair-minded and judicious employers.

Anyone who has worked in a sales call centre will know this is complete horse manure. In a centre I worked in in Belfast, where we were selling O2 phone contracts across Britain, with dodgily assembled data that had to be maximised before the impending GDPR introduction, we were trained and instructed to upsell from one SIM contract to four. Repeatedly.

One staff member was particularly skillful at this, and followed every instruction and quoted every term in the small print. He worked up to be in line for about £2000 worth of commission (on a £1300 per month salary). Then at approximately 16:50 on the Friday before the payslips went out, he and all the other staff who had earned commission were individually briefed that they would not be receiving any commission, because O2 didn’t approve of the upselling. (The timing is particularly devious – it means that the staff don’t share these stories of injustice, and inform each other what their collective and individual rights are, but also totally ruins your weekend, so you direct that toxic energy back on your loved ones, instead of the belligerents whose fault it is.)

The company still duly invoiced O2 for the successful sales, and bundled all the data together into a new, more valuable dataset of customers who answer their phones and are amenable to cold sales to be sold at approximately £3-5 per line. The sales associate had to explain to his daughter why she wasn’t getting the birthday present he had promised her.

NB These ‘jobs’ (read: professional public nuisances) were routinely celebrated as bringing in great employment to the area, and the companies opening these centres were usually rewarded by the likes of Invest NI through tax incentives, or straight up having invoices paid for them. In other words the risk was almost entirely removed — still these cretins ran a employment culture of rank exploitation of their staff and data. And this culture was widespread across every sales call centre in Belfast (probably Britain too but I can’t speak to that).

To suggest that the employees should bare personal responsibility for being aware of a company’s internal culture before they sign the employment contract is extremely onerous on job hunters who already have to parse whether location, salary, relocation and other factors make the employment worth it, based on information gleaned from a puffed up job advert (assuming they’re fortunate to be able to be choosy about such things).

Maybe it’s the employment culture that is broken?

I’m sorry to hear about your experiences!

The question is whether, once you’d discovered what the culture was like working for a firm who were making their money from employing, as you put it, “professional public nuisances”, did you depart?

Or did you stay and play by their rules?