There have been a couple of evenings recently when UK residents have been encouraged to go outside and clap and cheer for all our wonderful health workers who are doing such a great job. This is, in many ways, a good idea, and I would have joined in, had I known about them in advance! (We’re a little bit isolated out here and so didn’t hear about them until the following morning.) It’s all rather cringe-worthy, but a significant proportion of my family work for the NHS, and a large number of friends, and they’re working very hard in difficult circumstances. Some of them have come down with coronavirus themselves. So, yes, I probably would have overcome my natural reserve and clapped, at least if anybody other than passing rabbits would have heard me!

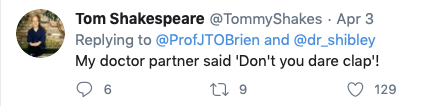

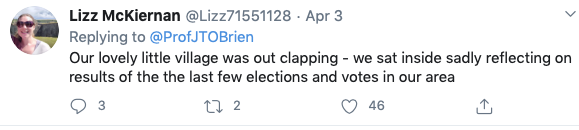

I was interested, though, today, to come across this thread on Twitter where a large number of people, mostly who work for the NHS or in healthcare, were expressing their discomfort with the idea, for a variety of reasons.

They had various motives, but the key one seems to be that politicians who have voted against increasing NHS funding have no right to praise those who are now having to be heroes as a result, and certainly not to lead the public in praising them in this low-cost way.

Others say that anyone who voted for those politicians should also not be outside clapping.

My view is that anyone who is not willing to pay a substantially increased personal tax burden should also have pause for thought. I’m guessing that, to have the service we’d all like, we should be thinking of paying about £1000 per year more per family member. (And yes, people who choose to have children would, and of course should, pay more.) However, the country as a whole has been given the opportunity to make rather more modest contributions than that on more than one occasion, explicitly earmarked for such things as health and education, and has turned it down.

I base that £1000 figure, by the way, on the fact that Rose and I have to pay rather more than that for a basic level of private health insurance, on top of what we currently pay for the NHS. We are fortunate to be able to do that, but it’s not because we’re particularly wealthy. We’re clearly a very long way from being poor, but we work for a university and are still, most years, basic-rate taxpayers, not high-rate. So this is a significant chunk of our income, and it’s a luxury but also a kind of voluntary taxation: yes, we get much better service, but in exchange we don’t have some other luxuries, and it doesn’t free us from paying for the NHS: we do that too. But we’ve placed much less burden on it, over the years, than we would have done otherwise.

If, by paying that amount to the NHS, I could be confident of all of us getting the improved level of service, I’d be happy to do so! Instead, at present, we pay so that thing are a lot nicer for us, and a little bit nicer for others.

The problem is that under-resourcing, though clearly a significant challenge, is certainly not the whole story.

On all three of the last three times I’ve had to go to NHS hospitals because friends or family have been there, I have been struck by the many wonderful, cheery, helpful workers… but also by the quite extraordinary levels of administrative incompetence. I encounter employees who would never be able to keep a job if this were a commercial enterprise. I experience procedures which, if they were followed so poorly in a business, would quickly result in that business no longer existing. (Though to be fair, that’s often true of many public bodies.)

And this, I’m sad to say, has been my almost constant experience. On both of the last two occasions I’ve had friends or family staying overnight in hospitals, they have occupied a bed for a whole day longer than necessary. Why? Not because they were still sick, but because the doctor literally forgot to come and discharge them before going home at the end of his shift. Two different hospitals. Two different doctors. Two different patients. Same problem. Actually three doctors, because one friend was forgotten twice in a row, though I think one of them might have been the nurse’s fault. They are not just short of hospital beds for lack of funds!

And this malaise is not just in the area of patient care. I remember when, as a struggling startup company, we were trying to sell a product to our local NHS hospital. They liked it, they wanted to buy it almost immediately, the cost was trivial, but it still took them more than a year to go through their procurement procedures and write us a modest cheque. Even then — and this was explicitly explained to me — they only managed to get it to us because somebody persuaded the person responsible for the relevant account to stay for a meeting which finished after 5pm. He was annoyed, and made it clear, because he normally went home soon after tea-time, at around 4.30pm. For those of us working long hours and weekends to produce the product, we just had to laugh. I know from talking to other technology providers that our experience was certainly not unique. But that was then – what about now? Well, now, remember this story when you hear that they can’t get the supplies they need.

These are just anecdotes, of course – I have no knowledge of the bigger picture on any statistically-valid level. I speak only of what I’ve experienced. But I have certainly not exhausted my stories: those are just a couple of the more worrying examples.

So yes, I love the NHS. I’m enormously grateful for what they’re doing now. And yes, I wish it were better resourced.

But anyone who thinks that somebody else will pay for a better service for them is living in cloud-cuckoo land; we all need to be willing to stump up significant amounts of cash. How many of those people out there clapping think that the problems now being experienced are all somebody else’s fault?

Anyone who thinks that money is the only problem, or that the politicians are the only problem, is similarly deluded. In this country it is very unpopular to talk about any degree of commercialisation of the NHS, and clearly that’s not a silver bullet: one only has to look at the costs of drugs in the USA for an example of how commercialisation can get out of hand.

But so far, nobody seems to have come up with a good way of instilling the disciplines and efficiency and levels of accountability that govern the commercial world into the public sector. And until they do that, it seems to me, we will continue to have some situations where we just have to rely on some people being heroes.

totally on the money!!

I would be interested to know how long your doctors who “forgot” had been on-shift when their memories slipped.

I suspect that were I to work the hours they do, I would be forgetting where the door was, never mind which of my numerous patients could be discharged.

This would be in stark contrast to your cheque-signer who liked to leave by 4:30pm. I work what I would consider normal hours but I have never finished that early: nominally 9–5 but if I’m in the middle of something I carry on until I’m done. My wife does finish around that time but only by dint of starting work before 7am.

I have long suspected that the NHS suffers mostly from midriff bloat: there are too many layers between those who toil at the coal-face and those who decide where to look for more coal, if you will forgive my stretched metaphor.

My mother worked for the NHS all her working life and she always says that things went downhill when the matrons were relieved of command. I suspect she might well be right.

[…] world, and especially those medical evils that are besetting us at the moment. As I pointed out in an earlier post, this is happening in many, if not most, countries — which should immediately give any […]

[…] I’ve written before about some NHS experiences that have convinced me that serious administrative incompetence is the […]