An interesting bit of data visualisation by Andy Kriebel gives some ideas.

I’d love to see how this varies for different countries/climates…

An interesting bit of data visualisation by Andy Kriebel gives some ideas.

I’d love to see how this varies for different countries/climates…

An intriguing article by Charles Duhigg, published a few months back in the New York Times magazine, talks about the value to large retailers of knowing when their customers are pregnant:

There are, however, some brief periods in a person’s life when old routines fall apart and buying habits are suddenly in flux. One of those moments — the moment, really — is right around the birth of a child, when parents are exhausted and overwhelmed and their shopping patterns and brand loyalties are up for grabs. But as Target’s marketers explained to Pole, timing is everything. Because birth records are usually public, the moment a couple have a new baby, they are almost instantaneously barraged with offers and incentives and advertisements from all sorts of companies. Which means that the key is to reach them earlier, before any other retailers know a baby is on the way. Specifically, the marketers said they wanted to send specially designed ads to women in their second trimester, which is when most expectant mothers begin buying all sorts of new things, like prenatal vitamins and maternity clothing. “”Can you give us a list?”” the marketers asked.

Well worth reading the whole thing. Gives a whole new ring to the phrase ‘targetted advertising’!

A good holiday is when you can't remember whether it's Sunday or Monday.

Most of you have probably heard by now about how the technology reporter Mat Honan’s accounts were hacked and how he lost his Google Mail, his Apple and Amazon account, his Twitter account and the contents of his iPhone and laptop. All in under one hour.

What’s fascinating about this story is that we know how it was done: there was no heavy brute-force attack on weakly-encypted passwords, no SQL injections on his company’s website. The hackers had no animosity towards him; they didn’t know who he was, they just liked his three-letter @mat Twitter ID. In other words, this could easily happen to you too!

If you haven’t heard the story, then I recommend listening to episode 364 of Security Now, which you can get from here or here. The discussion starts 30 mins into the programme.

You should probably listen to this if you, say, use the Internet…

“Can we arrange a time for a conference call with you?”, said the enthusiastic email that landed in my inbox last year from some company’s marketing department. “We're very excited to tell you about our new viral videos!”

To which my response, of course, was that if they were really viral, they wouldn't need to tell me about them!

I thought of this while watching Euan Semple's keynote from the State of The Net conference in June, which, in contrast, has a gentle, understated style yet includes some nice ideas that come from years of careful thinking about corporate communications, both internal and external.

Euan Semple is the author of Organizations Don’t Tweet, People Do.

On Aug 5th, the Curiosity rover landed on Mars. I hadn’t really absorbed, at the time, just what a technical achievement this was: not so much getting the thing to Mars, but landing it safely and ready to roll shortly after it hit the Martian atmosphere at 13,000 miles per hour. It weighs nearly a tonne. The Jet Propulsion Lab had, of course, made CGI simulations showing how the process would work, in advance of the landing, but in this brilliant piece of video editing they intercut it with footage of the control team on the ground celebrating its arrival. I suggest you turn the volume up and watch it full-screen.

Rose’s aunt used to work at JPL, and, when I visited many years ago, one of the directors made an offhand comment which basically amounted to a job offer. At the time, it was all very quiet, and though I was interested in the work, the elderly rows of SPARCstations tracking satellites didn’t grab me as particularly thrilling. Now, however, there can’t be many organisations that could put together a recruitment video like this!

It would be terribly presumptuous to think that my readers, not satisfied with whatever I might burble about today, might want to go on to explore the Status-Q archives…

However, the fact remains that there are over 2200 posts here now, and I certainly can’t remember everything I’ve written, so it’s fun for me, at least, to browse a bit. The ‘related posts’ at the bottom of each entry’s page often pop up things I’d completely forgotten, but now I’ve added a ‘From the archive’ box on the right: a completely random selection of five posts from the last decade, updated every few minutes.

Go on – have a browse. Whatever you find is bound to be more interesting than what you’re reading now!

Well, my tweets last night were mostly either bemused or rather negative, so I should emphasise that there were bits of the Olympic opening ceremony I thought were rather good.

I liked the levers of the industrial revolution hoisting enormous smoking chimneys into the sky, though one gets the impression that nothing good came from this Saruman-style destruction except the forging of five giant gold rings to rule us all. A pleasing effect, but some other industrial achievements might have been nice: Stephenson’s Rocket, perhaps? The spectre of Voldemort hovering over children in hospital beds, until chased away by Mary Poppins, was quirky but amusing, though perhaps he was really hovering over the NHS? It, like so much of the ceremony, must have been completely bewildering to hundreds of millions of viewers.

I cringed at some of the inevitable political correctness, was proud of the music we used to produce until about 20 years ago, was pleased by Her Majesty’s involvement in the Bond escapade and felt sorry for her obvious boredom at having to sit through the rest of it. It’s good that Tim Berners-Lee finally gets appropriate global recognition, tweeting ‘This is for everyone’ from the middle of the arena; given his natural humility it must have been a challenge to get him to agree. And the cauldron was, indeed, very pretty.

To give a true history of modern Britain, I thought, we should have had a huge influx of Polish people at the end! And then I realised that they had probably been there all along, behind the scenes, making everything work. And work it did; it was certainly an impressive technical achievement, and it looks very good in the BBC’s six-minute edited highlights.

Then the athletes came in, and many of them looked like rowdy drunken yobs coming out of… well… a sporting event. Still, I suppose that’s something else that the world knows us for.

Now, I know I’m not the target audience for this stuff; I’ve made my feelings clear about the financial outrage that is the Olympics. For the same money we could have given a shiny new MacBook Pro to every schoolchild in the country. Or employed 1000 teachers for 400 years. Or… well… take your pick of better investments. So I tried to divorce my feelings about the ceremony from its association with the bigger picture. And as my friend Jeff Jarvis put it, to set the context for his tweets last night: “I cannot abide opening ceremonies or folk dances”.

And I’m also very out of touch with popular culture – I recognised about half a dozen faces last night: the Queen, Rowan Atkinson, Sir Tim B-L, Daniel Craig and Kenneth Branagh. OK, five. But it would have been six if I’d stayed awake long enough to see Paul McCartney. So I imagine there were probably lots of sports personalities, soap-opera stars, rap ‘musicians’ and winners of X-Factor that might have been recognisable to others.

So it’s probably better to rely on others’ commentary than mine. I liked:

Allesandra Stanley in the New York Times:

It’s hard to imagine any other nation willing to make so much fun of itself on a global stage, in front of as many as a billion viewers. It takes nerve to look silly; the cheesy, kaleidoscopic history lesson that took Britain through its past, from pasture through the workhouses and smoke stacks of the Industrial Revolution to World War I and, of course, “”Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,”” was like a Bollywood version of a sixth-grade play.

But bad taste is also a part of the British heritage. The imagery mixed the glory of a royal Jubilee with the grottiness of a Manchester pub-crawl. Britain offered a display of humor and humbleness that can only stem from a deep-rooted sense of superiority.

…

The NBC anchors Matt Lauer and Meredith Vieira did their best to get in the spirit of British nuttiness, but at times their energy flagged, and their bewilderment became obvious. After a hospital sketch that morphed into a children’s nightmare — and a giant fake baby floating on a bed — Lauer said, “”I don’t know whether that’s cute or creepy.””

The whole show veered from cute to creepy and from familiar to baffling, including a pop music tribute to Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web. Most of all, it showed a love of movies that celebrate British eccentricity. “”Isles of Wonder”” seemed most inspired by a scene from the movie “”Love Actually,”” in which Hugh Grant, playing the prime minister, explains that Britain is still a great nation because it is “”the country of Shakespeare, Churchill, the Beatles, Sean Connery, Harry Potter, David Beckham’s right foot.””

Andrew Gilligan in The Telegraph:

Some of the rest was bitty and disjointed; the sub-mobile-phone advert style of the digital section was particularly weak. It was more political than I expected. Voldemort loomed over the NHS. Tonight marked perhaps its final transformation from a healthcare system into a religion. Dancers made up the CND symbol. The Royal Family looked bored, but the new Right-On Royal Family – Doreen Lawrence and Shami Chakrabarti – got to carry the Olympic flag.

The NHS segment in particular underlined how surprisingly parochial this ceremony was. The idea of the Health Service as a beacon for the world is, bluntly, a national self-delusion. Most other Western European countries have better state healthcare systems – and healthier people – than we do. Does the average Chinese person even know what the letters stand for?But I suppose the whole Olympics is in a broader sense parochial. Three weeks ago, I was in Libya witnessing that country’s first free election in sixty years: an end, or at least a beginning of the end, to decades of madness and tyranny which killed tens of thousands and blighted the lives of millions. To borrow the words of tonight’s over-excited TV commentators, that really was an inspirational and historic moment. Tonight, by contrast, was just a show.

One of my favourite podcasts at present is The Skeptics Guide to the Universe. Highly recommended, if you don’t know it. I liked this quote from a recent episode where they were discussing the Higgs particle:

“I read this great book about antigravity. I couldn’t put it down..”

The Telegraph reckons that it has inside information on what’s going to be included in the top-secret opening ceremony of the Olympics.

A stage backdrop of hills, streams, meadows and a thatched cottage will evoke Britain’s rural past. The landscape will be dotted with live animals, including 12 horses, three cows, 70 sheep, three sheepdogs and a horse-drawn plough, along with milkmaids, picnicking families, an Edwardian village cricket team in flannels, caps and braces, and people dancing around maypoles.

At one end of the arena will be a recreation of Glastonbury Tor, with an oak tree on top and a festival “”mosh pit”” at its foot. At the other end will be a space for crowds recreating the Last Night of the Proms.

It gets better…

…a third “”act”” of the ceremony will look at the post-war transformation of Britain, with models of Big Ben and other London landmarks, and a parade of dancing nurses and ancillary staff pushing hospital beds to represent the NHS and the Welfare State.

Oh good. Can’t wait for the dancing nurses.

…alongside 12,000 dancers, drummers, skateboarders, acrobats, and actors dressed as British historical figures, such as Emmeline Pankhurst, the suffragette, and the Caribbean migrants who arrived on the Empire Windrush in 1948…

I hope Emmeline Pankhurst will actually be on a skateboard.

I was just thinking that this could be a national embarrassment for which even the BBC’s reporting of the Jubilee River Pageant was insufficient preparation, when I suddenly realised that they must have a secret plan, because there is one way in which this could all be saved, could be put in the right context, and could turn the whole thing into a most enjoyable evening’s entertainment:

Get Terry Wogan to do the commentary.

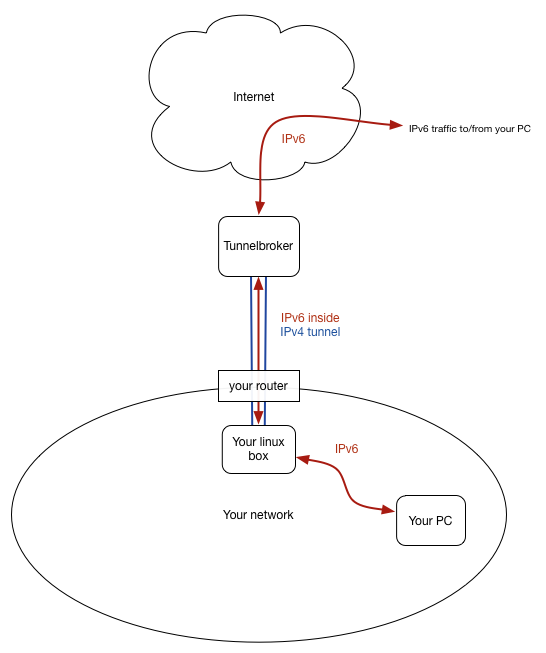

This is the third and (probably) final post in my series about enabling IPv6 on your home network. The first, Banish Mavis and Connect to the Future, explains the basics and why I think this stuff is really important. The second, Tunnelling your way to the future, tells you how, if you have a Linux box on your network, you can give full IPv6 connectivity to all your machines, even if your ISP doesn’t support it yet.

This is all great fun, but at the end of the last article I pointed out that there were also security considerations associated with making all of your machines accessible to the ravages of the outside world, and it was only something you should do if they had a modern operating system, up-to-date security patches, and were running a firewall. This may, understandably, make you feel a little nervous, so in this final section I’ll show you how to implement a simple firewall on the machine that’s acting as your IPv6 gateway, so you can choose what traffic you want to let in, from where, and to which machines.

This is still, by the way, very much better than the old NAT-based world of IPv4, because you are separating policy from capability: you can choose to allow SSH and HTTPS traffic to two different web servers inside your network, FTP access to one of them, and plain HTTP to a webcam, and give them all proper DNS addresses, while still blocking incoming connections to anything else.

As a simple example, I’m going to explain how to set up a firewall that allows incoming HTTP, HTTPS and SSH connections over IPv6 but blocks everything else, so you’re not at risk when, say, enabling file sharing between your home computers.

If you set up your system as per my description in the previous article, your linux machine is connecting to an IPv6 tunnel provider, receiving the IPv6 packets for your network on a virtual interface we called he-ipv6 and routing them out to your network over the normal ethernet interface, eth0.

Now, the way in which the Linux kernel routes data between interfaces is controlled by an internal table of rules, which is used to examine each packet and work out whether and how to send it on its way. These tables can be manipulated from the command line through a utility called iptables, or ip6tables for the IPv6 variant, and you could use these to set up the rules you need to let some stuff in and keep other stuff out.

It’s all very powerful, but unless you are part-robot yourself, trying to do much of this will make your brain hurt. This is the assembly-language equivalent of network configuration; you can make it do anything, and a very large number of the options you could choose will be the wrong ones. Eventually, you will get everything nicely set up, and all will be well until 18 months down the line when you have to change something and you have to remember what all those arcane lines of configuration were about.

So we’re going to use a system called Shorewall, which has a nicer way to describe what you want in a few simple configuration files, and then arranges all that iptables stuff for you behind the scenes.

We want the IPv6 version of Shorewall, so, assuming you’re on a Debian/Ubuntu-type system, you can install it with:

sudo apt-get install shorewall6

This will install both shorewall (the IPv4 version) and shorewall6, and will create configuration directories /etc/shorewall and /etc/shorewall6.

It will also put files to control the basic startup of each in /etc/defaults/shorewall and /etc/defaults/shorewall6. For our purposes, we can ignore the IPv4 version. There’s a line in each of these files that looks like:

startup=0

The firewall will not start up unless you change the 0 to 1, so do this in /etc/defaults/shorewall6 and leave the other one alone. The only other change you need to make to the defaults is to look for a line in /etc/shorewall6/shorewall6.conf that says:

IP_FORWARDING=Off

and change it to

IP_FORWARDING=On

otherwise the machine will stop operating as a router.

OK. Now we’re going to create four configuration files. Four?, I hear you squeak. Yes, four, but trust me, they’re wonderfully brief and straightforward. We’re just going to create them from scratch because they’re so simple.

Here’s how it works:

These are done in simple text files called:

/etc/shorewall6/zones

/etc/shorewall6/interfaces

/etc/shorewall6/policy

/etc/shorewall6/rules

See? At least the naming is nice and logical. There are man pages describing these in detail if you want to know more – just run man shorewall6-zones, man shorewall6-interfaces, etc. I’m certainly not an expert, having tried this for the first time today, but the following files work for me.

/etc/shorewall6/zones

This is just a list of zone names and types:

fw firewall

net ipv6

lan ipv6

/etc/shorewall6/interfaces

Specify where these zones live:

#ZONE INTERFACE ANYCAST OPTIONS

lan eth0 - tcpflags

net he-ipv6 - tcpflags

/etc/shorewall6/policy

By default, data from the firewall or LAN destined for the outside world is accepted. Data from the outside world is dropped. Everything else is rejected.

#SOURCE DEST POLICY

fw net ACCEPT

lan net ACCEPT

net all DROP

all all REJECT

At this point, you can start up the firewall to test it:

/etc/init.d/shorewall6 start

And you should then find that you can make outgoing connections, for example to ipv6.statusq.org, but not incoming ones. If you don’t have easy access to an external IPv6-capable machine, try using a service like this one on mebsd.com to ping one of your internal IPv6 addresses. It should fail.

/etc/shorewall6/rules

Finally, in this file, let’s define some rules to let in ping, http, https and ssh.

# These rules apply to all new connections

SECTION NEW

#ACTION SOURCE DEST PROTO DEST PORT

# Allow ping6 from outside world to firewall or LAN

ACCEPT net fw ipv6-icmp

ACCEPT net lan ipv6-icmp

# Allow http, https and ssh from outside world to firewall or LAN machines

ACCEPT net fw tcp 80,443,22

ACCEPT net lan tcp 80,443,22

That’s it! Restart your firewall:

/etc/init.d/shorewall6 restart

And you should now find you can ping, ssh or get web pages from machines inside your network, but all other incoming connections will be blocked. If you want to allow access to a particular machine instead of all of them, change the rule line to include both the zone and the IP address:

ACCEPT net lan:2001:470:1f39:1824:fa1e:dfef::d5dc tcp 80,443,22

Well done! There’s an amazing amount more you can do with Shorewall – have a look at the man pages – but that at least should give you the basics and let you sleep at night!

Feedback and suggestions welcome, as always: I’m a novice at this too.

In this longish and somewhat technical post, I’m going to tell you how to connect your home or office network to the brave new world of IPv6. Why would you want to do this, beyond the sheer joy of an educational experience, and having something cool to drop into the conversation at your next job interview? Well, if you haven’t seen it already, my previous post, ‘Banish Mavis and Connect to the Future’ , explains why this is more important than simply ensuring there are enough IP addresses to go around. At the end of the article, I’ll talk about some of the security issues you should be aware of in this brave new world!

The first thing to do is check that you haven’t got IPv6 connectivity already. Go to http://ipv6-test.com – a very handy site – and see what it says. It’ll probably tell you you’re connecting by IPv4 because, at the time of writing, very few ISPs have switched on IPv6 for their customers. If all goes well, you’ll be able to try this URL soon and get a different result!

On the other hand, you probably do have IPv6 capabilities on your local network, because most modern operating systems come with it enabled by default [1]. To see this for yourself, on Macs or other Unix-type machines, open a terminal window and type:

ifconfig

This will tell you about all your network interfaces; you can narrow it down by typing the name of the interface; for example, ifconfig en0 on the Mac or ifconfig eth0 on Linux will tell you about the first ethernet interface. Use en1 on Macs for a Wi-fi interface. What you’ll get is something like this (I’ve left out some of the unimportant bits):

$ ifconfig en0

en0: flags=...

ether 00:23:df:fd:9d:9b

inet6 fe80::223:dfff:fefd:9d9b%en0 ...

inet 192.168.0.23 netmask 0xffffff00 ...

status: active

You can see your IPv4 address, which probably begins with 192.168, and the unique ‘ether’ hardware (MAC) address of your network interface which is, at the very lowest level, how the network distinguishes one device from another. But there’s also an inet6 line showing an IPv6 address:

fe80::223:dfff:fefd:9d9b

In general, every network interface will have one of these fe80 addresses. They’re created automatically from the MAC address: if you look at the example above you’ll be able to see that some of the digit sequences occur in both the MAC address and the IPv6 address.

Now, you might quite reasonably think you could ping yourself using the ‘ping6’ command:

ping6 fe80::223:dfff:fefd:9d9b

but this probably won’t work. Why not?

Well, because all network interfaces, wherever they are, use the same fe80:: prefix for these automatically-generated addresses, we can’t use the normal routing mechanisms to work out automatically how to contact them. That’s why you’ll sometimes see addresses listed, as above, with a percent sign in them – it’s called a zone index and is generally followed by the local network interface you can use to contact that address. Try:

ping6 fe80::223:dfff:fefd:9d9b%en0

and you should see things happening. (Type Ctrl-C to stop it). You can ping the same address from another machine on the network but remember that the zone index – the name of the interface you’re going to use – may be different[2].

This is one of the many small cool features of IPv6 – there is at least one valid address that will let you contact a device on your local network, even if the device has never had one allocated by hand or by a DHCP server. This will be really handy in future when you need to set up some gadget out of the box by pointing a browser at it.

So, you have IPv6 on your local network, at least. It’s a bit like having a small railway system on your own island. But, until your ISP builds some bridges, you can’t use it to travel to the mainland unless you dig a tunnel. That’s what we’re going to do, and it is actually quite common at the moment, so don’t worry that you’re doing anything too eccentric!

The following process sounds a little complicated, but in fact it’s very easy once you understand what’s going on. The description is long, but the actions are few!

For the specific instructions I’m giving here, you need a couple of things:

If you don’t have these, don’t worry; most of what you’ll learn here can be tweaked to work on different systems. The important thing is to understand what’s going on.

To get connected, you’re going to need to setup three things:

radvd – the Router Advertisement Daemon – which is roughly the equivalent of DHCP.Here’s what we’re going to set up:

The best thing about all this is that it runs alongside your normal IPv4 system, which just keeps working as before, so it will only kick into action when you’re using IPv6, and won’t get in the way otherwise.

Go to http://tunnelbroker.net/ and register for an account, then click the ‘Create Regular Tunnel’ link. It’ll ask you for your IPv4 endpoint – this should normally be the public IP address of your router – that’s probably the IPv4 address you saw if you went to ipv6-test.com earlier. You’ll also need to give it a description, and pick a Tunnelbroker endpoint that’s close to you, for maximum efficiency.

Once you’ve created your tunnel, you can take a look at the details, which will be a page something like this:

The important bits here relate to the diagram above – make sure you understand these next two paragraphs. Look at the section marked IPv6 Tunnel Endpoints, and the tunnel illustrated in the diagram above. The Server IPv4 Address is the address of the Tunnelbroker end of the tunnel and the Client IPv4 Address is the public address of your end of the tunnel, generally the address of your router. The server and client IPv6 addresses are the addresses of the IPv6 link within that tunnel, as indicated in the diagram by the red arrow within the blue tunnel.

The Routed IPv6 Prefixes section, on the other hand, shows the prefix for the addresses that will be used on your network; the addresses that Tunnelbroker is going to route to your machines. These are very similar to but not the same as the addresses within the tunnel. They even use bold to emphasise the difference but it’s easy to forget and use the wrong one. When we set up the tunnel we’ll be using the addresses with 1f38 in them, and when we use radvd to advertise the addresses to use on your network we’ll be configuring it with the 1f39 addresses. In all the following examples, of course, you’ll need to put in the addresses specific to your tunnel.

OK, given that information, let’s log in to the Linux machine and start by getting it to talk to tunnelbroker. Edit /etc/network/interfaces and add your equivalent of the following:

auto he-ipv6

iface he-ipv6 inet6 v4tunnel

address 2001:470:1f38:1825::2

netmask 64

endpoint 216.66.80.26

ttl 255

gateway 2001:470:1f38:1825::1

dns-nameservers 2001:470:20::2 74.82.42.42

post-up ip -6 route add default dev he-ipv6

pre-down ip -6 route del default dev he-ipv6

This sets up the tunnel and creates a local interface called he-ipv6 that represents this end of it. We won’t go through all of it, but the last couple of lines – post-up and pre-down – tell the system that the default route for contacting the IPv6 world should be through this tunnel interface (and not, for example, through the machine’s ethernet interface which soon have an IPv6 address of its own.

The ‘auto he-ipv6’ command means that the interface, and hence the tunnel, will be started automatically when the machine boots up. For now, though, you can start everything manually with:

sudo ifup he-ipv6

and if all goes well, you can then take a look at it:

$ ifconfig he-ipv6

he-ipv6 Link encap:IPv6-in-IPv4

inet6 addr: fe80::c0a8:1e/128 Scope:Link

inet6 addr: 2001:470:1f38:1825::2/64 Scope:Global

UP POINTOPOINT RUNNING NOARP MTU:1480 Metric:1

RX packets:52042 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 frame:0

TX packets:35526 errors:0 dropped:0 overruns:0 carrier:0

collisions:0 txqueuelen:0

RX bytes:53875839 (51.3 MiB) TX bytes:5181848 (4.9 MiB)

This shows you your end of the tunnel, the IPv6 address ending ::2, and you can ping6 the other end, the address ending ::1.

$ ping6 2001:470:1f38:1825::1

PING 2001:470:1f38:1825::1(2001:470:1f38:18245::1) 56 data bytes

64 bytes from 2001:470:1f38:1825::1: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=18.2 ms

64 bytes from 2001:470:1f38:1825::1: icmp_seq=2 ttl=64 time=17.0 ms

[Ctrl-C]

You can try connecting to other places too, for example:

$ ping6 ipv6.google.com

If you have login access to another IPv6-capable machine – I used the server on which this blog is hosted – you can try pinging your Linux box from there. Remember, your Linux machine is at the local tunnel address, ending :2…

$ ping6 2001:470:1f38:1825::2

Hurrah! Your Linux machine, at least, now has a public IP address.

Incidentally, some utilities, like ping, have their own IPv6 versions – like ping6. Others, like ssh, will just use IPv6 automatically if given a v6 address. And some, like netstat, ip and route, will do IPv6 things if you specify an option, usually –6. So, for example, you can see your IPv6 routing tables with:

$ netstat -6 -r -n

OK, now we need to tell your Linux box to be a router for IPv6 traffic. There’s a line you need to add to /etc/sysctl.conf, and it may already be there but just be commented out. Uncomment it, or add it:

net.ipv6.conf.all.forwarding=1

You can reboot to make sure this setting is loaded, or run

$ sudo sysctl -p

which just tells the system to re-read the file.

One side effect of turning on routing is that it will disable the magic autoconfiguration of IPv6 addresses for the ethernet interface on that machine. That makes sense, really: you want the router to have a fixed address, in the same way that you don’t want your DHCP server to have a DHCP-allocated address! So we need to pick a static IPv6 address for your ethernet interface. On my network, the Linux box has an IPv4 address of 192.168.0.8, so I picked an IPv6 address with the ‘8’ at the end of it too:

2001:470:1f39:1825::8

Note the 1f39 here – we’re now talking about the local network, so we want the prefix to come from the Routed IPv6 Prefixes section of the tunnel configuration. I added some extra lines to /etc/network/interfaces to allocate this additional address to eth0:

iface eth0 inet6 static

address 2001:470:1f39:1825::8

netmask 64

You’ll have a section for eth0 already – this can be added separately because it’s configuring it for ‘inet6’.

You need to restart the eth0 interface to pick this up. If you’re logged in at the console you can do :

$ sudo ifdown eth0

$ sudo ifup eth0

but if you’re logged in by ssh this won’t work because you’ll be logged out by the first command! So you need to do them both at once: I tend check the details carefully and then get a superuser shell and run them like this:

$ sudo -s

root# ifdown eth0; ifup eth0

[ short pause, then hit return to check you still have a prompt ]

root# exit

$

If it worked, you can use ifconfig eth0 to see the new address.

So now your Linux box has a fixed IPv6 address on your local network interface and another one on the tunnel interface, and should be able to route traffic between them. We just need to tell the other machines on the network which IPv6 addresses to use, and that they should send traffic for the outside world to this machine.

On the Linux box, you need to get and install radvd:

$ sudo apt-get update

$ sudo apt-get install radvd

and configure it to advertise itself, and your network prefix, on your ethernet interface. Edit /etc/radvd.conf to say something like this:

interface eth0

{

AdvSendAdvert on;

prefix 2001:470:1f39:1825::/64

{

AdvOnLink on;

AdvAutonomous on;

};

};

Again, remember to use the right (routed) prefix for your local network. Then start up radvd, which on Debian would be

$ /etc/init.d/radvd start

or restart it if it’s already running.

And now, a magical thing will start happening! The other machines on your network will start to get, in addition to their `fe80:: addresses discussed earlier, automatically-allocated addresses in your own IPv6 prefix. Log on to another machine and have a look at ipconfig, or in the Advanced > TCP/IP section of System Preferences, or wherever, and you should see addresses beginning 2001.

In fact, each interface may have two of these addresses in addition to the automatic fe80 one. That’s because one of them is, like the fe80 range, based on the MAC address of the hardware. It is predictable and will always refer to that machine, and you can deduce the MAC address of the machine from it and vice versa. Some people are worried about the security implications of this: my laptop could be recognised as being mine, whichever IPv6 network I’m using it on. So on most systems there will also be a temporary address which is used by default for outgoing traffic and which is less traceable.

You should now find that the other machines on your network will show IPv6 connectivity if you use them to go to ipv6-test.com, or browse to ipv6.google.com, or indeed visit ipv6.statusq.org. And you’ll also find that they can be contacted from elsewhere; you can use an online ping test like this one to test it out. This is cool – you can setup a system to backup your webserver to your home much more easily now, for example. If you have a DNS domain, you can even go out and register a AAAA record for one of your home machines so you can contact it more easily from elsewhere, for example.

But the fact that your machines can be contacted from outside means we need to think about security.

If you decide to leave this system running, you need to be fairly confident about the security of your systems. Routers running NAT, for all their annoying limitations, did at least offer a convenient layer of security to your network, and you’ve now worked out a neat way to bypass that! I would certainly be cautious about doing this if you have machines on your network running elderly versions of Windows, or if you haven’t been keeping your machines in sync with the latest security updates.

I went around and turned on the firewalls on all of my machines – something I hadn’t bothered with beforehand, and I am now thinking more seriously about any file-sharing and other services I run on them. But I also have to balance any paranoia with the fact that almost all of my systems are Unix-based, and running very similar software to hundreds of thousands of publicly-accessible webservers out there, including mine.

The right way to deal with the security issues, of course, is to re-introduce filtering on the Linux machine that’s running your tunnel. You now have the option to let through any connections you like, to any machine on your network, but the default should probably be to block everything except perhaps ssh, and only open up extra options as and when required. This may feel like a return to the dark days of NAT, but in this case, when you do decide to allow, say, telephony traffic to your VoIP phone, you’re getting a proper end-to-end connection from one machine to another, and not depending on a cheap NAT router maintaing a table of temporary mappings.

Configuring Linux IP tables is not for the faint-hearted, though. I’ll have a look at whether there are any easy-to-manage systems out there that would be good for this kind of use. Any recommendations welcome!

Update: I’ve now added a tutorial on how to do this with Shorewall.

In the meantime, if you’re concerned and you’d like to disconnect when you’ve finished experimenting, just do an

$ ifdown he-ipv6

on the Linux box, and comment out the ‘auto’ line in /etc/network/interfaces so it doesn’t start up again on reboot.

Footnotes

On Windows XP you may need to install it first – it’s easy to find instructions on the web, but I won’t really focus on Windows here. ↩

On a Linux machine, for example, it will probably be %eth0 or %wlan0, on a Windows machine it will be something like %4, where the 4 indicates the number of the interface. ↩

© Copyright Quentin Stafford-Fraser

Recent Comments