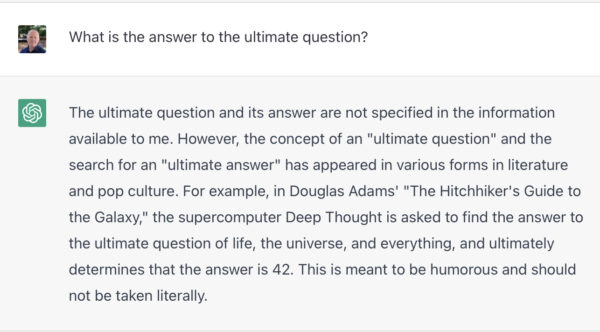

It’s important to keep finding errors in LLM systems like ChatGPT, to remind us that, however eloquent they may be, they actually have very little knowledge of the real world.

A few days ago, I asked ChatGPT to describe the range of blog posts available on Status-Q. As part of the response it told me that ‘the website “statusq.org” was founded in 2017 by journalist and author Ben Hammersley.’ Now, Ben is a splendid fellow, but he’s not me. And this blog has been going a lot longer than that!

I corrected the date and the author, and it apologised. (It seems to be doing that a lot recently.) I asked if it learned when people corrected it, and it said yes. I then asked it my original question again, and it got the author right this time.

Later that afternoon, it told me that StatusQ.org was the the personal website of Neil Lawrence.

Neil is also a friend, so I forwarded it to him, complaining of identity theft!

A couple of days later, my friend Nicholas asked a similar question and was informed that “based on publicly available information, I can tell you that Status-Q is the personal blog of Simon Wardley”. Where is this publicly-available information, I’d like to know!

The moral of the story is not to believe anything you read on the Net, especially if you suspect some kind of AI system may be involved. Don’t necessarily assume that they’re a tool to make us smarter!

When the web breaks, how will we fix it?

So I was thinking about the whole question of attribution, and ownership of content, when I came across this post, which was written by Fred Wilson way back in the distant AI past (ie. in December). An excerpt:

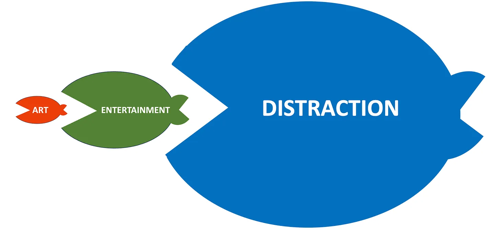

I attended a dinner this past week with USV portfolio founders and one who works in education told us that ChatGPT has effectively ended the essay as a way for teachers to assess student progress. It will be easier for a student to prompt ChatGPT to write the essay than to write it themselves.

It is not just language models that are making huge advances. AIs can produce incredible audio and video as well. I am certain that an AI can produce a podcast or video of me saying something I did not say and would not say. I haven’t seen it yet, but it is inevitable.

So what do we do about this world we are living in where content can be created by machines and ascribed to us?

His solution: we need to sign things cryptographically.

Now this is something that geeks have been able to do for a long time. You can take a chunk of text (or any data) and produce a signature using a secret key to which only you have access. If I take the start of this post: the plain text version of everything starting from “It’s important” at the top down to “sign things cryptographically.” in the above paragraph, I can sign it using my GPG private key. This produces a signature which looks like this:

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

iQEzBAEBCgAdFiEENvIIPyk+1P2DhHuDCTKOi/lGS18FAmRJq1oACgkQCTKOi/lG

S1/E8wgAx1LSRLlge7Ymk9Ru5PsEPMUZdH/XLhczSOzsdSrnkDa4nSAdST5Gf7ju

pWKKDNfeEMuiF1nA1nraV7jHU5twUFITSsP2jJm91BllhbBNjjnlCGa9kZxtpqsO

T80Ow/ZEhoLXt6kDD6+2AAqp7eRhVCS4pnDCqayz0r0GPW13X3DprmMpS1bY4FWu

fJZxokpG99kb6J2Ldw6V90Cynufq3evnWpEbZfCkCl8K3xjEwrKqxHQWhxiWyDEv

opHxpV/Q7Vk5VsHZozBdDXSIqawM/HVGPObLCoHMbhIKTUN9qKMYPlP/d8XTTZfi

1nyWI247coxlmKzyq9/3tJkRaCQ/Aw==

=Wmam<

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

If you were so inclined, you could easily find my corresponding public key online and use it to verify that signature. What would that tell you?

Well, it would say that I have definitely asserted something about the above text: in this case, I’m asserting that I wrote it. It wouldn’t tell you whether that was true, but it would tell you two things:

-

It was definitely me making the assertion, because nobody else could produce that signature. This is partly because nobody else has access to my private key file, and even if they did, using it also requires a password that only I know. So they couldn’t produce that signature without me. It’s way, way harder than faking my handwritten signature.

-

I definitely had access to that bit of text when I did so, because the signature is generated from it. This is another big improvement on a handwritten signature: if I sign page 6 of a contract and you then go and attach that signature page to a completely new set of pages 1-5, who is to know? Here, the signature is tied to the thing it’s signing.

Now, I could take any bit of text that ChatGPT (or William Shakespeare) had written and sign it too, so this doesn’t actually prove that I wrote it.

But the key thing is that you can’t do it the other way around: somebody using an AI system could produce a blog post, or a video or audio file which claims to be created by me, but they could never assert that convincingly using a digital signature without my cooperation. And I wouldn’t sign it. (Unless it was really good, of course.)

Gordon Brander goes into this idea in more detail in a post entitled “LLMs break the internet. Signing everything fixes it.” The gist is that if I always signed all of my blog posts, then you could at least treat with suspicion anything that claimed to be by me but wasn’t signed. And that soon, we’ll need to do this in order to separate human-generated content from machine-generated.

A tipping point?

This digital signature technology has been around for decades, and is the behind-the-scenes core of many technologies we all use. But it’s never been widely, consciously adopted by ordinary computer users. Enthusiasts have been using it to sign their email messages since the last millennium… but I know few people who do that, outside the confines of security research groups and similar organisations. For most of us, the tools introduce just a little bit too much friction for the perceived benefits.

But digital identities are quickly becoming more widespread: Estonia has long been way ahead of the curve on this, and other countries are following along. State-wide public key directories may eventually take us to the point where it becomes a matter of course for us automatically to sign everything we create or approve.

At which point, perhaps I’ll be able to confound those of my friends and colleagues who, according to ChatGPT, keep wanting to pinch the credit for my blog.

Recent Comments