John posted this lovely image from CultOfMac, showing phone designs before and after the iPhone.

As he says, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery…

John posted this lovely image from CultOfMac, showing phone designs before and after the iPhone.

As he says, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery…

Mac tip of the week…

The Spotlight search engine is a really useful feature of Mac OS X, providing an easy way to open your files, email messages etc. But suppose you want to do something other than open them: how do you find out where they actually are? Is it showing you the copy on your internal drive, or your external drive? What other things are in the same folder? Can I copy it onto a flash drive?

A quick note for new Mac users: the ‘Option’ key is labelled ‘Alt’ on some keyboards.

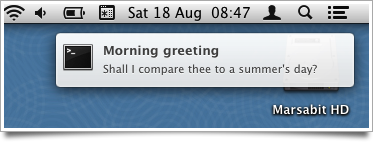

Here’s a handy utility for those using Mountain Lion’s new Notifications system (something I find I rather like despite never really getting on with Growl).

It’s called ‘terminal-notifier’ by Eloy Durán, and it lets you send these from the command line. So, for example:

$ terminal-notifier \

-message “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” \

-title “Morning greeting” -execute “open http://bbc.co.uk/weather/2653941”

This pops up a little notification, and clicking on it will take you to the BBC weather forecast for Cambridge.

You could put the command all on one line – I’ve just split it up with backslashes for readability. It’s easy to install terminal-notifier from the command line with:

$ sudo gem install terminal-notifier

Now, as an illustration of why it can be useful, I wanted this for a particular purpose:

I’ve been experimenting more and more with Multimarkdown, since so much of what I write ends up in HTML, and the markdown syntax is a convenient way to create it. I have an Automator service which takes the currently selected text, for example in a blog post text-entry field, parses it as Markdown, and replaces it with the HTML equivalent. I’ve assigned it a keystroke, so typically I’ll just do Cmd-A to select everything I’ve typed and Ctrl-Alt-Cmd-M to convert it to nice HTML. Very handy. It’s how I wrote this.

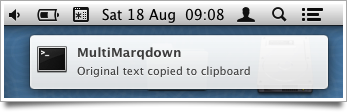

Just occasionally, however, I might want to go back to the Markdown version, so before conversion the selected text is also copied into the clipboard. This is the kind of quick temporary backup that becomes second nature if you have a clipboard history utility. But it’s easy to forget this has happened.

Now, I can just add a quick extra line in the automator script and I get a little pop-up to remind me, which vanishes again after a few seconds:

Thanks, Eloy!

Here’s what the Automator service looks like, in case anyone wants to do something similar:

A guy who worked on Mac repairs and maintenance told me a good way to test whether a Mac’s hard disk is working reliably. “Oh”, he said on the phone, “you can kinda stress-test it by opening the Applications folder and doing Cmd-A Cmd-O”.

It took me a moment to click just what he was saying: Cmd-A selects everything in the folder. Cmd-O opens things that are selected. In the case of apps, it will run them. So these two quick keystrokes will try to launch, simultaneously, every app installed on your machine.

“It usually takes 5 minutes or so, depending on the machine”, he continued. “But if there’s something wrong with the system this will usually find it.” Yes, I said, I imagined it would.

Now, I admit I haven’t tried this with my machines yet, but I did try it last time I was in the Apple store. And it’s a really good way to demonstrate the difference between hard-disk- and SSD-based machines!

Two things worth knowing if you try this experiment:

Nobody likes AppleScript. Well, almost nobody. It’s an attempt to make a programming language look like a natural language, which means that knowing what constitutes valid syntax in any given situation is almost impossible. I once suggested that what the world really needs is a Perl-to-Applescript translator, because Perl is a language that’s pretty easy to write but impossible to read, and AppleScript is easy to read but impossible to write. The syntax is a bit dependent on the apps with which you’re trying to interact, too, and the debugging options are exceedingly limited.

But the most annoying thing is that, on occasion, it’s exceedingly useful, and there aren’t really good alternatives for the kind of things it can do.

So just in case anyone out there is googling for this kind of thing, here’s how I made it change the default options on a dialog box that I use every day.

I’ve been inspired by David Sparks’s e-book Paperless, and my new-found fondness for the kind of things you can do with the Hazel utility, to get a better, more automated workflow for scanning in documents.

A key component, of course, is that you want them to be OCRed so that you can search for them, or search within them, later. I want something that does this automatically, or can be made to do it automatically, when a scan ends up in a folder on my disk, with minimal manual intervention. Good OCR programs are fairly costly on the Mac – Abbyy FineReader, at £79, is generally agreed to do the best OCR job, but the Mac version is not very scriptable. PDFpen, at £47, does a reasonable job and has better scriptability, and if I were starting now I’d probably use that.

But a while ago I splashed out on NeatWorks, which has good OCR, plays nicely with my wonderful ScanSnap scanner, and provides a complete filing system for my documents, with flexible metadata options. It’s a nice package. But the problem is that I no longer want a complete filing system for my documents – I want to do that myself.

So for the moment I’m using NeatWorks to capture my scans, OCR them, enter some metadata and then export them as PDFs to the folder where Hazel and other things take over. They typically stay in NeatWorks for about a minute.

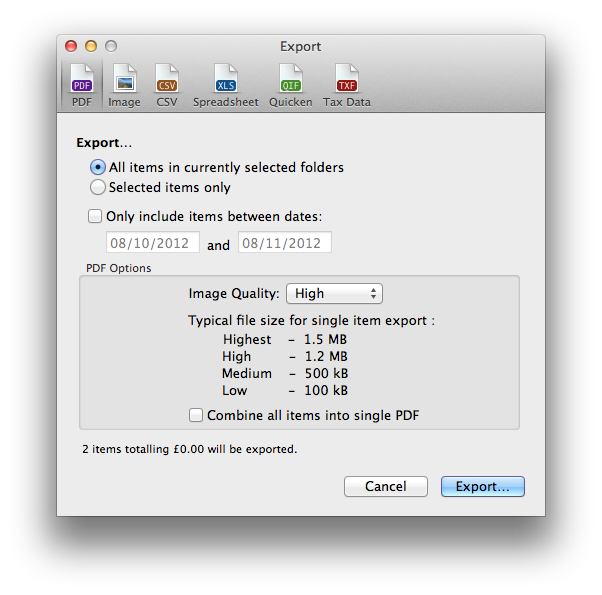

OK – that was a long run-up to explain why I regularly – often several times a day, do File > Export… and get this dialog:

At this point I can almost just hit [Return], except for one problem: the default is to export all the items in the currently selected folders and I just want to export the thing I last scanned. So every time I do this, I have to switch from keyboard to mouse, click the little radio button by ‘Selected items only’ and then carry on.

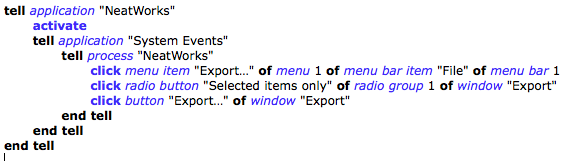

AppleScript to the rescue! I used Automator to create a service that just applies to NeatWorks and runs the following AppleScript:

This runs ‘File > Export…’, clicks the appropriate radio button, and then clicks the Export… button.

Finally I used the Keyboard section of System Preferences to assign a keyboard shortcut to this service.

Now, I drop some paper into the scanner and press the button on the front. NeatWorks pops up and OCRs it. I type in a title, document date and any other keywords I fancy, then just hit my magic keystroke and check the name and folder before hitting return to save.

At that point, Hazel takes over and does something like “if this file was created by NeatWorks, and has a name containing the word ‘Telemarq’ and the word ‘receipt’, then file it away in the appropriate folder of my receipts directory with a suitably reformatted filename”.

Well, OK, the title’s a little misleading, but here’s a very handy hint for anyone running Lion or later. It’s to do with moving files.

Though the Finder has, for a very long time, supported the copying and pasting of files from one folder to another, it has never allowed cut and paste. I could never fathom why something so simple wasn’t in there until I realised that, actually, there is a problem with implementing the concept cleanly: normally, when you cut things, they disappear. What happens if you cut a file but never paste it? Especially accidentally? (What happens on Windows? I forget…)

Still, this was an annoying omission, particularly if you’re used to Windows, or if you have a small display without much space for dragging things about.

Well, now you can do it. Instead of the normal cut & paste keystrokes (Cmd-X, Cmd-V) you do a copy and a kind of alternate paste (Cmd-C, Alt-Cmd-V). Intuitive? No. But I guess it makes a kind of sense.

Thanks to the excellent David Sparks for the hint.

There are a handful of utilities on my Mac that I use all day, every day. I’ve written about most of them before over the years — try the search box on the right — but since people liked some of my past posts about favourite iOS apps, I thought I’d gather these into a quick list here.

A tip for Mac users: The Library folder in your home directory contains miscellaneous preference files, support libraries etc, and most normal users seldom need to touch it, which is why it is hidden by default in Mac OS X Lion. The standard way to get to it, if needed, is to hold down Option while clicking the ‘Go’ menu in Finder, and it’ll appear among the list of destinations.

If, however, you’re not a ‘normal user’ you may wish to make it more visible, and this turns out to be very easy. Just open a Terminal window and type:

chflags nohidden ~/Library

And you should then see it in your Finder just like any other folder.

Thanks to MOApp for this one.

Mmm. I seem to have had a lot of hard drive failures recently – Seagate drives, mostly, though, to be fair, the majority of my drives are Seagate just because my favourite supplier happens to like them, so I would expect see more failures there. The last one, though, is just 18 months old and has started making ominous clicking noises. They don’t make ’em like they used to. Stuff I’ve read online tends to suggest that it’s hard to assign blame to particular drive manufacturers, but particular models do tend to have rather different failure rates.

Mmm. I seem to have had a lot of hard drive failures recently – Seagate drives, mostly, though, to be fair, the majority of my drives are Seagate just because my favourite supplier happens to like them, so I would expect see more failures there. The last one, though, is just 18 months old and has started making ominous clicking noises. They don’t make ’em like they used to. Stuff I’ve read online tends to suggest that it’s hard to assign blame to particular drive manufacturers, but particular models do tend to have rather different failure rates.

I do, I realise, have rather a lot of hard disks. I have three 4-bay Drobo enclosures, for a start, so that’s 12 drives even before I start adding on the miscellaneous backup disks, TV-recording disks, etc. Not to mention the internal ones in all our various machines. There must be 20-25 hard disks around here, and even though manufacturers’ specs talk about a <1% annual failure rate, studies tend to suggest that real-world figures are rather higher. One of the biggest studies, done by Google a few years ago, showed failure rates of 1.7% in the first year, rising to over 8% in the third year.

Yes, many of my drives are about that age, so if I really have 25 of them, I guess I should expect one to die every six months or so. Bother.

This suggests to me that money spent on things like my Drobo enclosures is worthwhile, because, though they are pricey, especially once you’ve filled them up with drives, any single drive failure is unlikely to be catastrophic – as disks die, you just replace them with whatever size is currently in vogue. My main Drobo currently has two 2TB drives, one 1.5TB, and a 1TB. There are those, I know, who have had less positive experiences with some Drobo kit – I found a DroboShare networking add-on to be decidedly wobbly at a past company – but in the simple use case of a Drobo plugged into a computer, I’ve been very happy and have replaced several drives without ever losing data.

The other thing that the Google study found was a strong correlation between when disks start reporting errors (which they can do using the S.M.A.R.T technology built into modern drives) and a failure soon afterwards. It’s worth, therefore, having something that checks the S.M.A.R.T status and lets you know about issues as soon as they are reported, even if the drive is still apparently working OK. On the Mac, Disk Utility can tell you about issues, but only when you go and look, so I use SMARTreporter to give more regular checks.

OK, things are getting better. There is another issue, though.

On the Mac, at least, most external drives are connected by USB or Firewire, and in general S.M.A.R.T information is not read through those interfaces – if you look in Disk Utility, you’ll see it’s ‘Unavailable’. More sophisticated enclosures like the Drobo will check the S.M.A.R.T status themselves and warn you when things look dubious, but your average USB-connected backup drive may give you no such warnings.

So I was interested to discover this kernel driver project which enhances the standard OSX USB and FireWire drivers to make S.M.A.R.T available for a lot more interfaces. (Download v0.5 here). I’ll try it on my Media Mac Mini, which has three external drives, and see how it goes…

Warning – technical post ahead…

My shiny new RaspberryPi came through the door this week, and the first thing I noticed was that it was the first computer I’d ever received where the postman didn’t need to ring the bell to deliver it.

My shiny new RaspberryPi came through the door this week, and the first thing I noticed was that it was the first computer I’d ever received where the postman didn’t need to ring the bell to deliver it.

The next thing I discovered, because it came sooner than expected, was that I was missing some of the key bits needed to play with it. A power supply was no problem – I have a selection of those from old phones and things, and I found a USB-to-micro-USB cable. Nor was a network connection tricky – I have about as many ethernet switches as I have rooms in the house.

A monitor was a bit more challenging – I have lots of them about, but not with HDMI inputs, and I didn’t have an HDMI-DVI adaptor. But then I remembered that I do have an HDMI monitor – a little 7″ Lilliput – which has proved to be handy on all sorts of occasions.

The next hiccup was an SD card. You need a 2GB or larger one on which to load an image of the standard Debian operating system. I had one of those, or at least I thought I did. But it turned out that my no-name generic 2GB card was in fact something like 1.999GB, so the image didn’t quite fit. And a truncated filesystem is not the best place to start. But once replaced with a Kingston one – thanks, Richard – all was well.

Now, what about a keyboard and mouse?

Well, a keyboard wasn’t a problem, but it didn’t seem to like my mouse. Actually, I think the combined power consumption probably just exceeded the capabilities of my old Blackberry power supply, which only delivers 0.5A.

If you’re just doing text-console stuff, then this isn’t an issue, because it’s easy to log into it over the network from another machine. It prints its IP address just above the login prompt, so you can connect to it using SSH, if you’re on a real computer, or using PuTTY if you’re on Windows.

But suppose you’d like to play with the graphical interface, even though you don’t have a spare keyboard and mouse handy?

Well, fortunately, the Pi uses X Windows, and one of the cunning things about X is that it’s a networked display system, so you can run programs on one machine and display them on another. You can also send keyboard and mouse events from one machine to another, so you can get your desktop machine to send mouse movements and key presses from there. On another Linux box, you can run x2x. On a Mac, there’s Digital Flapjack’s osx2x (If that link is dead, see the note at the end of the post).

These both have the effect of allowing you to move your mouse pointer off the side of the screen and onto your RaspberryPi. If you have a Windows machine, I don’t think there’s a direct equivalent. (Anyone?) So you may need to set up something like Synergy, which should also work fine, but is a different procedure from that listed below. The following requires you to make some changes to the configurations on your RaspberryPi, but not to install any new software on it.

Now, obviously, allowing other machines to interfere with your display over the network is something you normally don’t want to happen! So most machines running X have various permission controls in place, and the RaspberryPi is no exception. I’m assuming here that you’re on a network behind a firewall/router and you can be a bit more relaxed about this for the purposes of experimentation, so we’re going to turn most of them off.

Firstly, when you log in to the Pi, you’re normally at the command prompt, and you fire up the graphical environment by typing startx. Only a user logged in at the console is allowed to do that. If you’d like to be able to start it up when you’re logged in through an ssh connection, you need to edit the file /etc/X11/Xwrapper.config, e.g. using:

sudo nano /etc/X11/Xwrapper.config

and change the line that says:

allowed_users=console

to say:

allowed_users=anybody

Then you can type startx when you’re logged in remotely. Or startx &, if you’d like it to run in the background and give you your console back.

Secondly, the Pi isn’t normally listening for X events coming over the network, just from the local machine. You can fix that by editing /etc/X11/xinit/xserverrc and finding the line that says:

exec /usr/bin/X -nolisten tcp "$@"

Take out the ‘-nolisten tcp’ bit, so it says

exec /usr/bin/X "$@"

Now it’s a networked display system.

There are various complicated, sophisticated and secure ways of enabling only very specific users or machines to connect. If you want to use those, then you need to go away and read about xauth.

I’m going to assume that on your home network you’re happy for anyone who can contact your Pi to send it stuff, so we’ll use the simplest case where we allow everything. You need to run the ‘xhost +‘ command, and you need to do it from within the X environment once it has started up.

The easiest way to do this is to create a script which is run as part of the X startup process: create a new file called, say:

/etc/X11/Xsession.d/80allow_all_connections

It only needs to contain one line:

/usr/bin/xhost +

Now, when the graphical environment starts up, it will allow X connections across the network from any machine behind your firewall. This lets other computers send keyboard and mouse events, but also do much more. The clock in the photo above, for example, is displayed on my Pi, but actually running on my Mac… however, that’s a different story.

For now, you need to configure x2x, osx2x, or whatever is sending the events to send them to ip_address:0, where ip_address is the address of your Pi. I’m using osx2x, and so I create the connection using the following:

Once that’s done, I can just move the mouse off the west (left-hand) side of my screen and it starts moving the pointer on the RaspberryPi. Keyboard events follow the pointer. (I had to click the mouse once initially to get the connection to wake up.)

Very handy, and it saves on desk space, too!

Update: Michael’s no longer actively maintaining binaries for osx2x, and the older ones you find around may not work on recent versions of OS X. So I’ve compiled a binary for Lion(10.7) and later, which you can find in a ZIP file here. Michael’s source code is on Github, and my fork, from which this is built, is here.

I love Skype – it’s one of the most-used utilities on my Mac, and a vital business tool.

I love Skype – it’s one of the most-used utilities on my Mac, and a vital business tool.

There are some who don’t understand this, chiefly because they think Skype is about making cheap phone calls. Of course, it’s very good at that too: I dread to think how much I might have clocked up in phone bills on my last holiday if I hadn’t had Skype and the hotel wifi network. It’s also the easiest way I know to set up conference calls.

But mine is configured so that when I double-click on a name, it pops up a chat window, not an audio connection. Though, I admit, the first thing I type is often ‘Are you free for a quick call?’ But that’s so much more polite and… well, British… than simply bursting a ringing phone into someone’s day without so much as a ‘by your leave’.

At other times, the chat window is all I want. I can drop quick text messages in there, like ‘Can you remind me of the login for this URL?’, and it’s generally quicker and less hassle for everyone involved than any other way of transferring that information.

The real power comes when you’re combining the two – a conversation and a chat window. If you’ve ever tried dictating a URL to someone so that you can peruse a web page together while talking on the phone, you’ll appreciate the power of a cut, paste and click to keep things moving along. And, gosh, I haven’t started talking about video calls, about screen-sharing, about file transfer… And the fact that, if you’re willing to pay a few pence, you can send text messages from it, which is so much easier than typing on a phone keyboard.

Anyway, the degree to which you too will discover this brave new world of communicative wonderfulness depends on two things:

Skype first became really important for me when one of my former companies was headquartered in a house with a studio in the garden. Half of the team worked in the house, and half in the shed, so having a quick, lightweight method of communication between the two was important.

When we outgrew that, we moved to an open-plan office. Open-plan offices are things that people used to think were a good idea because they hadn’t tried them. Then commercial landlords realised that it was a much more convenient way to let out office space, so they told their clients, “Oh yes, everybody’s doing this now”. They still continue to exist because the people making the property decisions aren’t writers or software developers, who need peace, quiet and concentration, punctuated by a modicum of social interaction over caffeine-dispensing equipment, to be really productive.

So, in many offices, you have big open spaces filled with people wearing headphones and listening to music loud enough to drown out the distractions of the phone calls around them. They’re more isolated than if they were in different rooms. Managers seem to like this arrangement, because when they walk in they see large numbers of people beavering away, and they fail to realise that those people are beavering about two-thirds as efficiently as they might beaver. Factor that into your rent-per-square-foot…

Anyway, I digress, but the result was that Skype continued to be important when we were all in one room, not to talk to people at the far end of the garden, but for reaching those who were just a couple of desks away but in a completely different musical genre.

If you spend much time sitting in front of a computer, you owe it to yourself to run Skype and get your friends and colleagues doing so too. Yes, there are other systems, but few that run on Windows, Linux, Mac, Android and iOS and give you such a variety of different communication styles.

One final tip for Mac users: the current version of Skype, version five-point-something, is generally agreed to be horrible. Well, not horrible, exactly – in fact, I think it looks quite nice – but it does have ideas above its station and wants to take over your entire desktop. Fortunately, this feeling that it’s got just a bit too big for its boots is so widespread that the previous version, 2.8, is still available from the Skype website on its own download page a couple of years after its supposed replacement was rolled out. Grab a copy and make a backup, in case it goes away…

© Copyright Quentin Stafford-Fraser

Recent Comments