I’m slightly amused by all the news reports this week that the government wants a ‘national conversation’ on the future of the NHS. While this is a laudable idea which will appeal to the punters, I doubt it’s actually very practical.

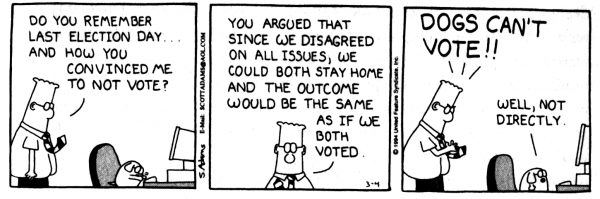

My late friend Martin King used to say that the ease of making any decision is inversely proportional to the number of people involved in making it. So trying to have a committee of 70 million people might be counterproductive? Anyway, Martin’s theory was that you shouldn’t, in general, try to make any decisions in meetings; you should only use them to ratify decisions you have already made!

A wise man, in many ways.

My own view of how to fix the NHS, for what it’s worth (and I admit it’s not worth very much, probably!) is as follows:

Firstly, it needs to be more tightly integrated with social care (so people can get out of hospitals quickly), secondly, it needs much better ways of rewarding efficient and effective workers and getting rid of others (because of the often amazing administrative inefficiency and incompetence of many otherwise lovely and well-meaning people), and thirdly, of course, it always needs more funding. (Oh, and fourthly, we should re-join the EU, but I’m not holding out much hope there…)

So let’s talk about funding. We should be completely open with the public about how much more funding is needed. My guess, based on the cost of private healthcare plans, is about £1-2k more per person per year. We currently spend just under £4k/person/year on healthcare.

I wrote more about this topic a couple of years ago. Note that, despite much common rhetoric, the NHS has never actually had any cuts in funding, except once, when the increased spending during Covid returned to its normal levels after the pandemic. But the rate of growth in spending has varied under different governments. This interesting page from the BMA suggests that, under the Conservative government, there has been an cumulative ‘underspend’ of £446bn, which they base on the fact that the longer-term historical rate of growth (a pretty substantial 3.8% in real terms) hasn’t been maintained at the same rate in the last decade and a half. If it had, they would have had that much more.

It sounds like a terrifying figure, but it’s only £6K per person, or £400 for each of those years, to recover all of it. Another interesting observation is that we spend the same proportion of GDP on healthcare as most other comparable countries. It’s just that our GDP hasn’t been doing very well lately! (So I guess the counter-argument would be that we get the NHS we can reasonably afford, and we need to fix the economy to get a better one.) But let’s assume, for the purposes of argument, that we want to fix the NHS and we can’t immediately fix the economy.

We should then simply propose adding whatever amount is really needed to income tax or NI. There are far too many people who complain that the NHS is underfunded but assume that the funding is going to come from somebody other than themselves!

For people to accept this, these funds should be ring-fenced, so they really can’t be spent on anything else. Then we should just make people vote on whether they really want it, based on the extra x% of tax it’s going to cost them, either through a referendum or as a manifesto at the next general election. (Count me in, for all reasonable values of x!)

Actually, a referendum would allow the extraction of real numbers for x. Imagine going to your polling station and being presented with just one multiple choice question; something like this:

How much should the government raise the current standard rates of income tax for the exclusive purpose of further funding the NHS and Social Care systems? (choose one answer)

- Not at all

- 1%

- 2%

- 3%

- 4%

- 5%

Then you do the maths and give people the NHS they’re willing to pay for. The ballot box, I would suggest, may be the only way to make a decision when the participants in your ‘conversation’ are truly ‘national’ in their numbers!

Otherwise, Martin’s law applies.

P.S. I do know that some of the above is over-simplistic. Historically, raising overall tax rates hasn’t usually actually raised overall revenues for any length of time, for example, but I think raising them for this explicit purpose, and then cutting them elsewhere if you want to, would prove popular. However, I’m not an economist, and you should feel free not to vote for any government proposing to appoint me as Chancellor or Health Secretary,

Recent Comments