A few years ago, the ‘University Information Services’ (UIS) team at Cambridge made the decision that the University would no longer run its own email service — something it had done since email began — and instead was going to outsource it to a commercial entity.

This in itself, I think, was probably a mistake, because email is enormously important, not just as a communication method, but as an archive. Many people make this mistake. “We use Slack for our internal chat, we use Facebook and Twitter and WhatsApp and Zoom for our external communications. We hear some old people still use email, but why is that any different?”

Email, though, for most people, is not just an instant-messaging system. It’s a store, a journal, a database, a record, of decisions made, invoices received, relationships formed, ideas generated, news exchanged, and so on. I have most of my email for the last thirty years or so, and find it incredibly valuable. Last year, I wrote a post about why I think it’s one of our most successful and important data archive formats, and its success for so long, when compared with almost anything else, has depended substantially on open standards and Open Source software.

Running an email server is easy. Doing it well, however, is not, and requires expertise and dedicated staff. In the past, I have run my own personal server, and we also did this in one of my startup companies. (In both cases these were based on the excellent, widely-used and highly-regarded Exim software which was, ironically, developed here at Cambridge in that same UIS department!) But these days there are lots of good hosting services, and it doesn’t normally make sense for most organisations to run their own.

The University of Cambridge is not, however, a small organisation, and surely it should really be willing to employ the skilled staff and provide the resources to run its own email system, in the same way that it runs its own libraries. (Maybe they’ll be next?)

However, out-sourcing is the name of the game these days, and it’s not that that is causing me, and several of my colleagues, concerns.

Exchanging open for closed

No, it’s the fact that that the University decided to opt for Microsoft Exchange Online. A couple of days ago, most staff who had not yet transitioned were moved from our own servers to Microsoft’s, and the forced migration will be complete by the end of next week, and the old servers switched off at the end of the year. For most people, in the short term, this will just be a minor inconvenience. So why does this worry me? Because I take a longer view.

No, it’s the fact that that the University decided to opt for Microsoft Exchange Online. A couple of days ago, most staff who had not yet transitioned were moved from our own servers to Microsoft’s, and the forced migration will be complete by the end of next week, and the old servers switched off at the end of the year. For most people, in the short term, this will just be a minor inconvenience. So why does this worry me? Because I take a longer view.

Since email was invented, all of the email of many tens of thousands of University staff and students has been stored in formats defined by open standards, on machines that we control, generally by open email software running on open operating systems which were storing it on open filesystems… and so on. We had full control, and we always knew we could manipulate, improve, archive, extract and back up any part of this system which stores such a valuable archive of data for the entire community.

This week, however, saw the transition of that entire archive to a system running proprietary software, stored in proprietary formats on proprietary operating systems and filing systems, on servers that we no longer control. And the most important question, of course, when putting any important data into any new system is “How easily can I get it out again, in a usable format for the future, if I change my mind?”

Now, normally, one of the many wonderful things about an IMAP-based email archive is that this is trivial: you can decide to move it from one hosting service to another, or just shift it to your own machine, simply by dragging and dropping it using the email program of your choice. I have done this many times over the decades, as I’ve moved between jobs, email providers, academic institutions, and also as my email-reading devices have switched between different operating systems and different email apps.

Exchange, however, has always had problems supporting IMAP access to email reliably. Experts disagree on how serious those problems currently are, but the fact that the debate continues is worrying. It’s a lower priority for Microsoft, because they’d rather you used their own protocols and their own software.

The slippery slope

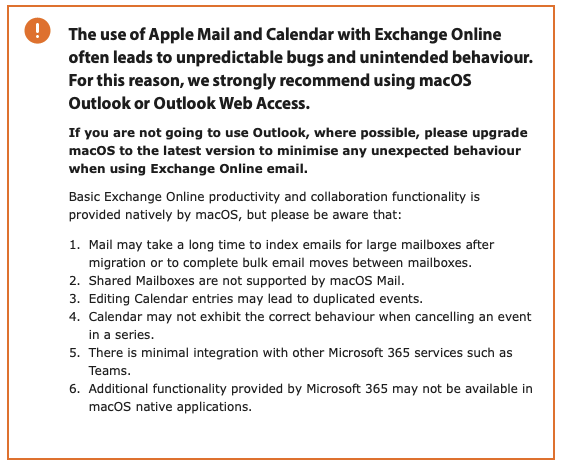

The UIS’s own pages telling Mac users how to connect to the new email service, for example, start with this dire warning:

Note that this is referring to Apple Mail, one of the most-used email clients in the world, and there’s a similar warning for those accessing their email and calendars from iOS devices.

What hope is there for those of us who prefer less-common email clients, such as my long-term favourite, Mailmate? Or who use less-mainstream operating systems? Or who have older hardware that won’t run the latest software?

This rings alarm bells for those of us who remember Microsoft’s (thankfully failed) attempts in the past to control another open system — the Web — by getting people to run Microsoft software both on the desktop and the server. When you control both ends of a system, you can freely modify the protocols used to communicate between them until it becomes very hard for users to adopt any other system. Microsoft used predatory and sometimes illegal business practices in the past to try and kill off Netscape and other desktop competition in pursuit of this goal, but the overall strategy failed, partly because their own server-side software was so inferior to the Open Source offerings that the techies responsible for most web servers refused to depend upon it.

I hope we are not seeing a repeat here — and to be frank, I doubt it — but I do wonder whether this shift to Exchange will prove to be a one-way-only transition. Suppose Microsoft were to say, in a few years’ time, that only a very small proportion of Exchange users now depended on IMAP, and they would be switching it off shortly. What options would the University have?

And what choice would users then have about the software they ran on their desktop to access this valuable archive?

Could we rely on getting thousands of email archives out and into a usable form elsewhere? What about any enhanced metadata? Attachments? Calendars? Contacts? There are open standards for all these things, but what incentives would Microsoft have to ease that transition, if it were even viable?

No, I fear that this contract, once made, has been made for ever.

And some of the implications are starting to be felt elsewhere. It recently came to light, for example, that the contract with Microsoft covered the staff and students of the University, but we have traditionally continued to provide email cam.ac.uk addresses to retired academics, emeritus professors, others helping with the activities of the University. “Ah”, said Microsoft — after the deal was signed, as I understand it, but perhaps before our chaps had cottoned on to all the implications — “You do realise that they’re not included in this deal?”.

This has made a lot of people very upset, because they had been given to understand that the email address that they’d always had, often the only one they’d ever had, that had been published at the top of their academic papers for decades, and had been used, for example, to set up all of their other online accounts, would remain a valid way of contacting them indefinitely. Not any more. This, of course, is standard practice in the business world: you leave a company and your email address is gone. The company closes, or is bought, and your email address is gone. But ancient universities haven’t always been run on those purely corporate lines or with those same expectations of transience.

Where does this leave us?

Essentially, therefore, there has been only one choice for those of us who wish to keep our email in standard formats that we know will be accessible in the long term. Reliable archiving is not a service we can now expect our eight-century-old University to provide, so we take all incoming email to our University addresses, and forward it to our own accounts held elsewhere.

Many of my colleagues in the Computer Science department are now doing this. We have to hope that this will continue to be allowed, both by the University and, of course, by Microsoft. We can’t ignore the Microsoft servers completely, because they will probably soon also be the only way to send email that will be recognised by the outside world as coming from a valid cam.ac.uk address. And being able to receive email under such an alias can be important for accessing academic journals, university service etc.

But some friends have decided that a better option is to start using their own personal email addresses on academic projects, papers, websites etc. to ensure that they have control in the future. (If you’re doing this, make sure you use your own DNS domain or a long-term reliable forwarding service, so you aren’t indefinitely tied to your current ISP or your ancient Hotmail account for your future professional communications!)

me.com

And perhaps some of this is inevitable. I used to rely on my employer to provide me with a telephone and a telephone number, for example, but the one sitting on my University desk for the last several years has almost never been used.

For many of us, it’s important that we control our own ‘brand’. Our own phone number, our own website, our own LinkedIn pages are more important to us than how we appear on any particular employer’s website, and as a result we need to pay for those out of our own pockets. Email should perhaps be the same, and wise academics should probably ensure that they control their own destiny and don’t use their current university email address on their publications.

But it all gradually erodes the sense of belonging to an ancient institution with which you might have a lifelong relationship. And that isn’t good for the institution either, especially when it comes to fund-raising. Ask any development office.

yeah… but all is well now that the University has published its new email policy proposal, which asserts that expecting to own an @cam.ac.uk email address perpetually was bonkers anyway.

I particularly love how they have to ignore how publications and role addresses work, just because the only hammer Redmond gave them ties email addresses to identities.

For now? The University of Edinburgh has recently followed up its own switch to Microsoft mail services with default removal of the possibility to automatically forward email. It’s under an Information Security Policy expressing concern about the risks of breaching UK GDPR/DPA2018 data protection regulations. I’ll be interested to see whether Cambridge ends up with a similar decision.

Mmm. Interesting. If we go out of our way to encourage people not to use our university email address at all, then I guess it solves their GDPR problem if it doesn’t even pass through their servers… 🙂

Also, if this is the cause of outlook being the main email system encouraged for students then this has brought the scourge of all email clients into the forefront of interactions done by students who don’t want to set up their own email solution.

I mean seriously, the online implementation of outlook is beyond useless. It is horrific at formatting, and so slow it is difficult to believe. Somehow, it seems to not register typing on my keyboard properly, by missing out random letters, and is so slow that it has actually made me late before, by taking several minutes to look up an email.

Compare to gmail, which runs smooth and fast on the same computer.

I have no idea how they made outlook that bad, but it is somewhat impressive.

I retired from Cambridge University several years ago and kept my Cambridge email address. The recent migration included retirees and I successfully migrated to Exchange Online last month. Having said that, I have always used other email addresses, for different purposes (currently three others) and don’t rely on the Cambridge one.

There is an email services cam-ac.org which was setup by ex-Cambridge employees as an independent email service.

There was a time when the University ran everything on SUN microsystems using Linux.

I find it even more telling that the people who made the original decision to transition the university off open systems, in spite of protests, petitions and measured evidence that this would be worse, have taken up plushy appointments elsewhere.

Funny how they never seem to stick around long enough for their decisions to take effect.

How much is the University paying for this service, and what protection does it have against Microsoft doubling the price every couple of years? If it had outsourced to a generic IMAP provider, the protection would be the simplicity of migrating again to a more competitive provider, but migrating from ExOL looks tricky.

Yes, it should. But when you factor in all of the costs – not just hardware, power, and staff, but also a backup system, secondary site for resilience, high-speed connectivity and so on – you generally find that the University’s colleges and departments aren’t prepared to pony up sufficient cash for all of that to happen. It’s funny how quickly the desire for something evaporates when people are asked to actually pay for it…

You have also overlooked the rather key point that IMAP is unsuited to the ever-increasing demands of giant mailboxes. Particularly if, like yourself, you’re dealing with three decades’ worth of content, now expanded beyond just email to include all of your attachments, calendars, contacts and all the rest. Even message headers have ballooned in size since spam-prevention became a consideration. Please think back to when you first gained the use of email, hosted by your own department: how big was that first mailbox? How big is it now?

Microsoft’s academic licencing model starts with a 50GB mailbox, and the next tier up is 100GB. Many academics can fill that space comfortably and need an archive on top.

The limitations of IMAP, and the slowness you mention in Apple’s email clients, needs to be considered as like-with-like. If your mailbox genuinely does remain a similar size to your original on-premises Exim mailbox, I’m certain that Microsoft’s implementation of IMAP would cope admirably with it. But if, as I strongly suspect, your mailbox has bloated a little over the years, then perhaps you should consider if it’s Microsoft’s implementation of IMAP, or the sheer volume of content you’re asking IMAP to deal with that is the issue.

Matthew –

Good points, but in fact, though I do think the university ought ideally to run its own email service, my concern is not really about outsourcing but with the fact that it’s outsourced to Microsoft, whose track record on supporting open standards is dubious to say the least — especially when it comes to Exchange — and who have very little incentive to make sure that this is anything other than a one-way transition into their proprietary world.

I might think that you had a point regarding IMAP, which is certainly ancient — except that the other IMAP services I use have no problem with my (currently 24GB) archive.

If the University had decided to outsource the email to, say, Fastmail, I would have had no complaints, and, in fact, some groups within the University have now arranged to do just that in order to avoid Exchange.

[…] glad that I didn’t invest any serious time in any Gmail-specific features! You may have seen my article a few months ago about why I, and a significant number of my colleagues, will no longer keep important data in our […]

[…] necessarily be able to go back and search indefinitely. For that, it’s still better to use standards-compliant email… or to copy the important stuff into your personal Knowledge Management System. You do have […]

[…] the requirements of most power users, all without having to sell your soul to, say, Google, or use nasty proprietary systems like Outlook. Yet your email is still completely accessible using standards-compliant IMAP etc when you want […]