My parents live about 13 minutes’ drive from the nearest hospital. There’s also a more substantial one 20 mins away. Over the last few years, they have on several occasions needed to call an ambulance after falls and other serious issues, and the waiting time is always measured in hours; on a couple of occasions, more than eight hours.

This shocks me, but it shocks my American wife even more. When they had to call an ambulance for her mother in Michigan — a fairly regular occurrence in her later life — they would worry that something was wrong if it hadn’t arrived in twenty minutes, because normally it was there in about ten. For all the outrageous costs and several other failings of the American health system, there are some things it does do rather well.

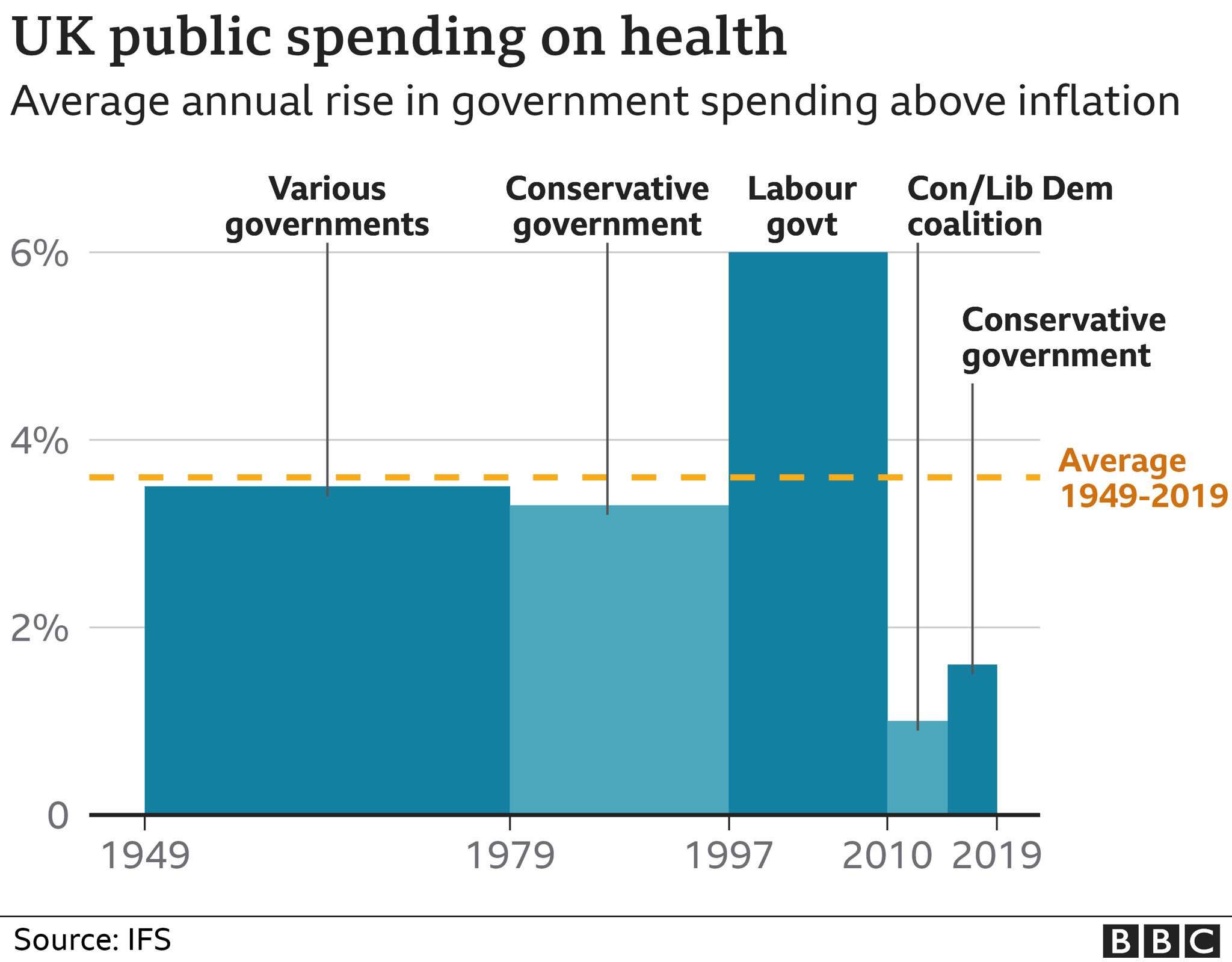

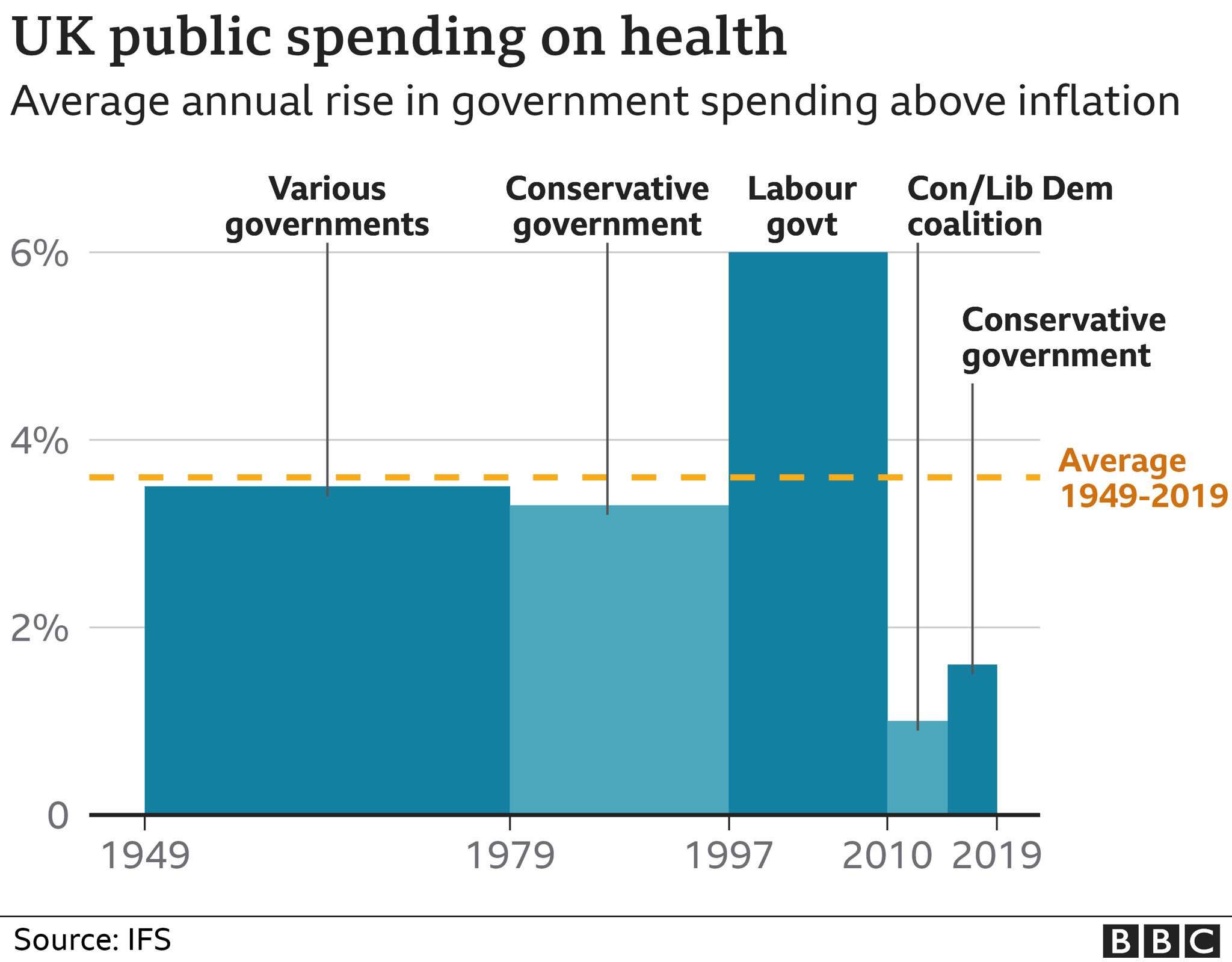

The simplistic public response to the NHS problem is to blame under-funding. “It’s because of Tory cuts!” Here’s a graph that was popular on Twitter last year, for example, and looks pretty damning:

But let’s be clear about what this graph shows: this is expenditure growth, above the rate of inflation. In other words, since its foundation, every government has given the NHS significantly more money in real terms every year. Some have increased it faster than others, but there have never been any ‘cuts’, from Tories or anybody else. So, while more money is desirable, that’s not the primary problem.

(As an aside, we all love the story of Captain Tom Moore who so caught the public imagination by his sponsored walks around his garden between his 99th and 100th birthday that he raised a whopping £33M for the NHS, earning him a knighthood, an honorary doctorate and an RAF flypast on his 100th birthday. It was a great feel-good story during the pandemic, and I don’t want to take anything away from his achievement by pointing out that he, and all his millions of sponsors, funded the NHS for a total of about an hour and a half. The world would be a much better place with more Captain Toms in it, but a whole battalion of Toms are unlikely to make a significant difference to the NHS.)

Now, I’ve written before about some NHS experiences that have convinced me that serious administrative incompetence is the source of many of its issues. And, to the extent that proper funding is also needed, I pointed out, it simply requires us all to vote in a government that is going to charge us about £1000 more per family member per year, and earmark that exclusively for the NHS. The UK public has only very occasionally been given the option to do something like that, even on a more modest scale, and they have never voted for it.

So I was intrigued by John Burn Murdoch’s analysis in yesterday’s FT. (The page itself is probably behind a subscriber paywall.) He provides the usual worrying statistics about A&E and ambulance waiting times, but points out:

While the pandemic has undoubtedly created a shock in the UK’s publicly funded health system, the NHS’s underlying issues are chronic. Waiting lists for elective treatment have been lengthening for 10 years, and the target of keeping 95 per cent of A&E waits under 4 hours missed for just as long.

…

It would be easy to blame underfunding, but in 2019 the UK spent just over 10 per cent of GDP on healthcare, placing it among other wealthy western European countries. The trend over the past two decades has also aligned with comparable nations, according to the OECD.

The key problems, he suggests, are also not simply with staff shortages:

While the number of fully qualified permanent GPs in England has fallen by 8 per cent since 2009, that of hospital doctors has grown by a third, outpacing the growth of the elderly population that accounts for an outsized portion of hospital demand. Nurse numbers continue to grow despite more departures this year.

In other words,

… ever growing resources are being used to treat ever more sick people, but ever fewer are being used to prevent them from getting sick in the first place.

The UK ranks among the highest for admissions to hospital for some conditions which would, in other countries, be largely treated within primary healthcare. (I am reminded of my wife’s surprise that GP practices in the UK don’t generally have X-Ray machines: you have to go to hospital for a check on a minor fracture!)

Anyway, the first part of his proposed solution is that we need to rethink the balance between primary care and hospital care; this is more of an issue than overall funding levels.

And the second is that it’s easy to blame staff shortages, but studies have shown that A&E delays, for example, are primarily about physical capacity — especially bed capacity — in the rest of the hospital, and are not significantly affected by staffing levels.

In summary, he says,

Much like any chronic illness, the NHS’s afflictions will not be cured with a sticking plaster. The road to recovery is paved with long-term investment to upgrade the physical capacity of the system, and to gradually shift the balance from treatment in hospitals to primary and preventive medicine.

A nicely-written article, and one of the many reasons I would pay for an FT subscription if the university wasn’t kind enough to do so for me.

Update, about six months later: There’s a very interesting page at the BMA providing an overview of current health spending in the UK and how it compares to other countries, and to the past history of the NHS.

A few years ago, I came across a really useful rule-of-thumb for calculating electricity cost:

A few years ago, I came across a really useful rule-of-thumb for calculating electricity cost:

Recent Comments