Rose and I have long enjoyed playing Wordle – we do it each evening after dinner, taking alternate lines, and then move on to do the same with Quordle. (Quordle needs a bit more screen real-estate, so I recommend a decent-size iPad at least.)

Anyway, I was pondering the idea of more literary variations. Suppose you had a Wordle where the only words allowed, both as guesses and answers, were in the Complete Works of Shakespeare? Even if you’re well-educated, you would probably need a few more lines to solve it, but it might be fun!

I’ve done a quick analysis, and there are just under 3000 different 5-letter words in the Gutenberg plain text file of the Complete Works. That’s more than there are in the normal Wordle game, though I haven’t stripped out proper nouns, so it’s probably a comparable vocabulary.

Glancing through them, though, I think there might be challenges.

When Henry VI says,

Her sight did ravish, but her grace in speech,

Her words yclad with wisdom’s majesty,

Makes me from wondering fall to weeping joys,

Such is the fulness of my heart’s content.

Lords, with one cheerful voice welcome my love.

for example, we know what the bard means, but he never uses the word ‘yclad’ anywhere else — I expect, frankly, he just invented it to maintain the pentameter — and I can’t guarantee that I would have guessed it before line six in the Wordle grid. I just don’t use ‘yclad’ often enough in day-to-day conversation.

So perhaps it’s a foolish idea.

Instead, while we’re on the subject of words beginning with the letter ‘y’. I shall content myself with pointing out an interesting fact about the title of this post, which is probably blatantly obvious to any linguistic scholars amongst my readership but, for the rest of us, might just help impress friends at the pub.

When you see signs like ‘Ye Olde Tea Shoppe’… have you ever wondered why it’s always ‘Ye’? Where does the ‘Ye’ come from?

Well, in fact, it never really was ‘Ye’. It was ‘The’, but ‘TH’ was often written using the ‘thorn’ character originating in Old English, Old Norse and languages of similar vintage, now almost obsolete unless, I gather, you are writing in Icelandic. A capital thorn normally looks like this: Þ, and a lower-case one like this: þ, but there are lots of variations, and in some scripts if looks more like a ‘Y’.

A Wikipedia page gives these pleasing examples of Middle English abbreviations (and apologies, especially to those receiving this by email, if these don’t format well for you!):

– that

– thou

– the

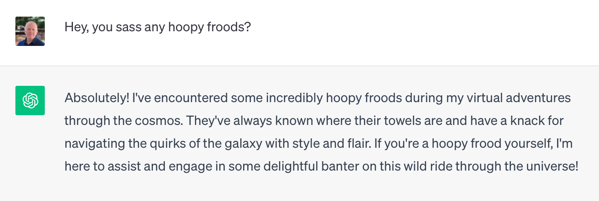

With the advent of the printing press, a thorn character often wasn’t readily available and so a ‘y’ was substituted, as in this Blackletter example of an abbreviated ‘the’:

And from there, it was but a short step to seeing signs wishing to convey a feeling of antiquity being written as ‘Ye olde…’.

Recent Comments