Two things keep reminding me that I’m in America and not Britain:

- Firstly, no signature or PIN is needed on card transactions less than $50.

- Secondly, completely filling my petrol tank from empty yesterday didn’t even get close to that amount.

Two things keep reminding me that I’m in America and not Britain:

I’m exceedingly proud to count Rose Goslinga amongst my friends.

On 1st October, the tax disc that British cars need to display in their windows is being abolished, nearly a century after it was introduced. Not the tax, you understand, just the disc.

On 1st October, the tax disc that British cars need to display in their windows is being abolished, nearly a century after it was introduced. Not the tax, you understand, just the disc.

The various government web sites talking about this say that it’s no longer needed ‘because of the electronic register’. They don’t tend to mention the CCTV cameras which now check your number plate much more reliably than the traffic wardens who used to check your tax discs.

This all makes good sense – it should help dramatically reduce the number of uninsured drivers on the road, for example – but it will no doubt also feed the fears of the conspiracy theorists…

There are more costly ways to light your home than by installing Philips Hue lightbulbs — you could, for example, send your butler on trips around the world to gather various species of fireflies, bring them back and cultivate them in custom-made crystal chandeliers — but I suspect not very many.

There are more costly ways to light your home than by installing Philips Hue lightbulbs — you could, for example, send your butler on trips around the world to gather various species of fireflies, bring them back and cultivate them in custom-made crystal chandeliers — but I suspect not very many.

For those who haven’t come across them, these are mains LED bulbs that you install in place of traditional ones, but with the added benefit that you can change both their brightness and their colour remotely, from an app on your phone or tablet. Now, I am a serious gadget enthusiast, and I liked the sound of these when they first appeared, but I quickly dismissed them, for several reasons.

First, did I mention that they are expensive? By expensive, I mean £45-50 per bulb. Yes. Per bulb. They come as standard-shape bulbs with screw-fittings, or as those little GU10 spotlights which are so trendy nowadays. Got six of them in your dining room? That would mean… well, you can do the maths. If you don’t already have low-energy bulbs, you can make an argument that they’ll pay for themselves in a few years, but most of us have already had to switch, and my previous attempts at buying expensive LEDs have not been encouraging: the majority of them have failed within about 18 months.

Secondly, they seemed, well, a bit childish. I loved playing with multi-coloured light bulbs in my bedroom when I was 12 years old. But now, well, I don’t really want the house to look like a night club or bordello. It’s sad, but, as an old married couple, we seldom have the kind of parties for which red and purple glows in the corners of rooms are needed.

And then, of course, they come with screw fittings, which is terribly European, but in Britain we tend to have those somewhat-annoying bayonet sockets, unless, that is, we bought most of our lights at Ikea.

And finally, do I really want to pull out a phone, unlock it, find and start an app, just to turn the lights up or down? What will my wife, Rose, do, since she almost never carries her phone, and has only started up about three phone apps in her life?

No, in the end, I thought, it’s easier just to stick to our nice dimmer switches, and buy up stocks of incandescent bulbs from Amazon to use with them, for as long as the EU will let us.

And yet, I had some nagging doubts.

You see, I kept hearing good things about the Hue system from people who had it. “I bought a starter kit to play with and I now have 14 bulbs!”, said one person. “One of the few Internet-of-things products that just works out of the box”, said another. It was a bit like when I finally bought Sonos speakers, or a ScanSnap scanner – both were expensive decisions that I’ve never since regretted. People who have these things, on the whole, really like them.

But – and this was the key issue – I was very aware that this, or something like it, has to be the future.

Assuming we are not going to restrict ourselves to the simple on/off switch for all our future lighting — even if we don’t want colour-changing bulbs, but just dimmable bulbs — then we have a problem with our current model. LEDs cannot be effectively dimmed simply by turning up and down the voltage, as we used to do with hot filaments. Yes, you can buy ‘dimmable’ bulbs which try to work with existing dimmer switches, but it’s a bodge, a stopgap at best – they never do a very good job.

No, the right way to do this is clearly to separate the power circuitry from the control. In an ideal world, we’d probably run four wires to each lightbulb instead of two or three, but retrofitting that to any existing building would be a nightmare. So we have to keep the power lines, ignore or remove the old light switch, and use another method to control the brightness, such as a wireless signal. Now, once you can control the brightness of an individual LED, it’s very easy to put red, green and blue ones in a single package and control them individually, which means you get colour control almost for free. At the simplest level, companies like Auraglow make bulbs which come with a remote control: you can change the colour from anywhere in the room by pressing a little button on the channel-changer. It’s a fun toy. But any lighting system that’s going to stand the test of time needs more than that.

I know what I want from my ideal lighting system. It needs to be managed through the network. I want the lighting to respond to timers, to motion sensors, to external events, to IFTTT rules. In an ideal world, it would have a nice open programming interface, so lots of people could write software to control it, and my house wouldn’t depend on one iPhone app. Ideally it would use one of the established wireless standards, rather than yet another proprietary protocol, so there’s some chance it could interact with other devices using the same standard. I’d like the communications to be two-way, so different components could find out what the state of the lighting is now, and not assume that they already know; that they are the only things interacting with it. And it would be helpful if there were libraries for some of my favourite programming languages so that writing my own software, if it proved necessary, would be easy.

And the more I thought about this, the more I realised that Philips had already built my ideal lighting system.

It was very expensive, but I can’t imagine Edison exactly gave away his bulbs at the start of the last lighting revolution, either. I was willing to pay for quality. And I was definitely willing to pay to experience the future.

So I ordered the three-bulb starter kit, which includes a gateway that connects the system to the network. I explained to my long-suffering wife that this was part of experiencing the future, and she smiled at me in a bemused way that made it clear that (a) she was used to this kind of thing by now and (b) she fortunately had no idea of the financial outlay involved.

So I ordered the three-bulb starter kit, which includes a gateway that connects the system to the network. I explained to my long-suffering wife that this was part of experiencing the future, and she smiled at me in a bemused way that made it clear that (a) she was used to this kind of thing by now and (b) she fortunately had no idea of the financial outlay involved.

Converting them to fit in our bayonet sockets turned out to be an easy process, and I started to play. Within a very short period, I had ordered three more bulbs.

The first thing I found out is that changing colour is very valuable, but not because I wanted patches of purple kitchen. For me, it’s about subtle changes of colour temperature: morning light to high noon to evening glow to tungsten coziness. More about that later.

The only more saturated colour I use is a dim red (I call it ‘low glow’), which we turn on when heading to the TV room to watch a movie – it feels like the low light in cinema corridors. The lights on the landing also switch automatically into this mode at about the time we’re heading for bed, so that any late-night pottering about is done in a rosy dimness that makes me think I’m in a submarine, about to surface and not wanting to destroy my night vision. Run silent, run deep. A little while after midnight, they fade out over a 15-min period, so I don’t have to get up to turn them off.

It was even reasonably wife-friendly, since you can reset the bulbs in the time-honoured way: by turning them off and then on again. They lose their settings and come back with a pleasant warm white. Others have complained about this: if you have them in the bedroom, and there’s a power cut during the night, you’ll certainly know when the power comes back on! But for me it was a feature. All good so far. But it gets better.

You see, there was still the problem of having to reach for a gadget whenever you wanted to interact with them. I knew that this would prove to be too much of a nuisance, and we’d end up just flicking the light switch off when we left a room, which would destroy a big part of the experiment: I wanted to see whether we could usefully automate our lights so that you wouldn’t need to turn them on and off: most of the time they would just be at the right level. And you can’t do that if they’ve been switched off at the power source.

Fortunately, there was a solution on the horizon for this, too: the Philips Hue Tap, a four-button switch which can be programmed to select different scenes, and which has a couple of really nice features: firstly, it can be unclipped from its mounting plate, so you can put it on the coffee table or kitchen workshop if wanted, and secondly, it needs no batteries! The button presses need to be fairly firm, but that’s because it harvests enough energy from them to transmit the signal. These were still tantalisingly unavailable on Amazon UK, but someone in a newsgroup mentioned that they had found one at their local Apple store. I popped into town and, sure enough, there they were. Not actually on the shelves, which were looking a little bare — “Someone just came in and bought enough kit to do their entire house!” — but they still had some in stock at the back. I went home with two, and they work beautifully.

Fortunately, there was a solution on the horizon for this, too: the Philips Hue Tap, a four-button switch which can be programmed to select different scenes, and which has a couple of really nice features: firstly, it can be unclipped from its mounting plate, so you can put it on the coffee table or kitchen workshop if wanted, and secondly, it needs no batteries! The button presses need to be fairly firm, but that’s because it harvests enough energy from them to transmit the signal. These were still tantalisingly unavailable on Amazon UK, but someone in a newsgroup mentioned that they had found one at their local Apple store. I popped into town and, sure enough, there they were. Not actually on the shelves, which were looking a little bare — “Someone just came in and bought enough kit to do their entire house!” — but they still had some in stock at the back. I went home with two, and they work beautifully.

The next excitement is that there’s a new bulb coming soon: the Philips ‘Lux’ – which allows you to control the brightness but not the colour, and costs about half as much as the Hue. We have a few ceiling light-fittings which take two bulbs, and equipping each of them with Hues would be decidedly pricey. So I have some Luxes on pre-order, which Amazon should deliver in a week or two. That was always really my intention: the Hues were a frivoulous experiment, I thought.

In the intervening time, though, I’ve found I really like the colour-changing abilities. I’ve always tried to get low-energy bulbs to be as ‘warm’ as possible, so they feel comparable to incandescent bulbs. Some people like a very white light, but in general I don’t want to feel as if I’m in an operating theatre. Now, though, I’m discovering that different colour temperatures are good at different times of day. The problem with a warm tungsten glow is that it is clearly an artificial warm tungsten glow. Our upstairs landings have no windows, so we often need lights switched on during the day, and having a very different colour of light from the outside world somehow emphasises the fact that there are no windows. Now, for most of the day, we just turn on some daylight, almost as if we’ve installed an extra window.

I, of course, think that it’s fun to be able to turn the entire house into a submarine by pressing a single, non-battery-powered button. But I knew that this whole experiment might be a longer-term success the day after I installed the bulbs, when Rose (who normally tolerates, rather than embracing, my high-tech projects) volunteered a comment over dinner. “I have to admit”, she said, “it was really quite nice having that daylight in the hall outside my study today.”

Yes, the system has its flaws — the cost, the limited range of bulbs, some quirks in the standard app — but I think it also has many qualities which point to what the future of lighting will be. And the fact that it has this degree of spousal acceptance — so far, at least — suggests it may also point to what the future of our lighting will be as well!

My programmable remote control has shortcuts for various activities:

For the last year or so, ‘Watch live TV’ has been relegated to the second page… and I don’t think I’ve used it…

I have no idea whether Sir Cliff Richard really had some indiscretions a quarter of a century ago with someone marginally under the legal age limit, and frankly I don’t care.

What I do care about is the way our legal system now favours trial by “twelve good tabloids and true”. Geoffrey Robertson’s excellent article in the Independent describes how the law works for celebrities now. Worth reading.

There’s a rather charming, and thought-provoking, video here. A reporter goes to the Ivory Coast, meets with some cocoa farmers, and gives them something they’ve never had before…

Chocolate.

John Naughton’s Observer column this week discusses the leaked plans for Amazon’s ‘Kindle Unlimited’ service.

Amazon’s move will be as discombobulating for the book publishing industry as the advent of Spotify was for the music industry.

The analogy is a good one. Creative content is being commoditised: as a rough approximation, you can’t make money from selling music any more, only from going on tours. You can’t make a living from selling photos, only from running photography workshops. And for some time it’s been pretty rare for anyone to be the family bread-winner by writing books — you also need to teach creative writing at the local Further-Ed college — but I think it’s going to become much rarer. Expect authors to start charging a lot more for their appearances at literary festivals.

And, lest you think, “Oh, this isjust a wild idea from somebody in marketing that was leaked by accident”, it has now been launched in the US. Six quid a month for all the books you can read, available instantly.

Just think what those monks in the scriptoria would have said.

On episode 191 of Mac Power Users, (at 32:58) I described how I found it useful to be able to visualise the various steps of my automated ‘paperless workflow’. (Something I also wrote about here on Status-Q last year.)

A few people asked for more details, so here’s a 9-minute screencast going into some of the lower-level stuff.

Also available on Vimeo for the media cognoscenti!

Like most people who own Sonos kit, I’m a big fan of my loudspeakers and amps. They work beautifully, and sound great.

Like most people who own Sonos kit, I’m a big fan of my loudspeakers and amps. They work beautifully, and sound great.

However, I suspect most of their users would be less interested than me to discover that by pointing a browser at ip_addr:1400/status I can discover, for example, which version of the Linux kernel each loudspeaker is running, and the fact that they seem to incorporate an accelerometer.

I couldn’t do that with my old record deck, now, could I?

If we’re right that there are 100,000 or more intelligent civilizations in our galaxy, and even a fraction of them are sending out radio waves or laser beams or other modes of attempting to contact others, shouldn’t SETI’s satellite array pick up all kinds of signals?

But it hasn’t. Not one. Ever.

Where is everybody?

That question (or a variant of it) is known as The Fermi Paradox, and the above quote is taken from this rather nice and very readable article which outlines some of the big questions and possible answers.

Many thanks to Michael Fraser for the link.

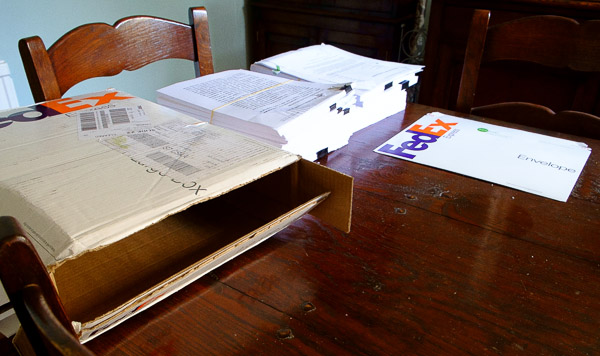

Some patent lawyers sent me a few bits of paper this week.

I reckon there’s well over 1000 pages here, shipped at, I imagine, vast expense all the way from Atlanta to my recycling bin here in Cambridge. The big box in the foreground brought them here. The slim envelope in the background is for returning the half-dozen pages that actually need my signature.

I’m not blaming this particular firm for this foolishness: they are probably obliged to provide me with hard copies by some outdated regulation kept in existence by extensive lobbying from FedEx and Xerox. But you’d think they could find an alternative. Like emailing PDFs. Especially since (a) I don’t need to read them to sign the bits of paper and (b) their client is Google…

Anyway, now you know where the trees have gone.

© Copyright Quentin Stafford-Fraser

Recent Comments