I discover that what has been happening to my waistline recently is perfectly normal and natural, and lots of other people are being tested for it too.

It’s called ‘lateral flow’.

I discover that what has been happening to my waistline recently is perfectly normal and natural, and lots of other people are being tested for it too.

It’s called ‘lateral flow’.

Ah, take a deep breath of those lovely aerosols!

I’ve always disliked open-plan offices, and viewed them as a conspiracy between property owners (who can pack more employees into a given space and have to do less reconfiguration for each new tenant) and over-micro-managing senior staff, who want to keep an eye on all the people working for them and ensure nobody is slacking. I’ve disliked them even when I’ve been one of those managers.

Under certain circumstances, yes, they can generate an exciting buzz of activity. We’ve all seen movies where the journalists or the detectives are dashing in and out and calling to each other about how they’ve just been summoned to Downing St, or to another murder, or whatever. But for anything requiring sustained contemplation or concentration they are, in my experience, dreadful.

This is especially true if the overall number of people is too small. We once made the mistake of taking on an open-plan space when one of my companies had about 12-15 employees, and it meant that everybody had to listen to everybody else’s phone calls, and the only way software developers could get work done was to wear headphones most of the day: more isolating, in many ways, than if they’d had their own office spaces.

But, since I’ve been fortunate enough to escape such working environments recently, it hasn’t occurred to me until now to wonder what contribution this open-plan trend has made to the spread of Covid!

At the University department where I’ve spent part of my time for the last few years, we typically have offices with two or three people in them, and so by carefully managing the number of people in a space at any one time, those who want to return to work have been able to do so much more easily and we could, if wanted, get a reasonable density of building-occupation without too much risk, and without everyone having to spend the whole day wearing masks.

But when I think back to a temporary role I had in London a couple of years ago, in a big shared space with about 120 other people, I wouldn’t want to go anywhere near that office now, even after my third jab.

Are any of my readers still doing the open-plan thing? How does it work in a Covid world?

Back in about 1993, I was doing the bookkeeping for a big project being undertaken by my local church. Donations were flooding in, and we needed to keep track of everything, send out receipts, forms and letters of thanks, and note whether each donation was eligible for the UK tax relief known as ‘Gift Aid’.

Back in about 1993, I was doing the bookkeeping for a big project being undertaken by my local church. Donations were flooding in, and we needed to keep track of everything, send out receipts, forms and letters of thanks, and note whether each donation was eligible for the UK tax relief known as ‘Gift Aid’.

I was keeping track of this using on a PC running the now long-gone Microsoft Works, which, for those less familiar with last-millennium computing, was a software suite incorporating basic and much cheaper versions of the things you found in Microsoft Office: a word-processor, database, and spreadsheet. If your needs were simple, it worked rather well.

Anyway, at one point I was printing out a list of recent donations on my dot-matrix printer, and I noticed what appeared to be some data corruption. In the midst of the sea of donors’ names, there were a couple of dates being printed out. Was this a software bug, or was my database file corrupt? I started investigating, while wondering just how much data I’d entered since my last backup and whether I could recreate it…

In the end, the answer was simple, and I breathed a huge sigh of relief. I tried recreating the entry for one of donors and the same thing happened again, at which point I dug a bit deeper and discovered a ‘feature’ of the app. The lady’s first name was ‘June’, and, though it displayed just fine on the data-entry screen, behind the scenes, it had been turned into 1/6/93! I skimmed quickly through the congregation to find the other problematic record, and found it was for a donation from a lady named ‘May’!

When I came back to doing some scientific computing in academia a few years ago, I was surprised and slightly worried to see several of my colleagues processing their data with Excel. It’s a wonderful program and very appealing, because of the ease of viewing, checking and plotting graphs of your results, but it comes with lots of problems of its own and shouldn’t be used as a substitute for a proper database (if you’re a church accountant), or for something like Jupyter Notebooks, if you’re a scientific researcher, unless you’re exceedingly careful. Last year, more than a quarter of a century after my issues with May and June, 27 human genes were actually renamed because of the number of errors caused in scientific papers by the use of Excel by researchers. The genes’ previous names were things like ‘SEPT1’.

All of this came to mind when reading Tim Harford’s enjoyable piece in yesterday’s FT, The Tyranny of Spreadsheets. Harford follows the origins of spreadsheets, double-entry bookkeeping and other ways of keeping track of things, up to the famous case last year where 16,000 people weren’t promptly told they had positive Covid test results, because somebody had used Excel’s old XLS file format, which can only store about 64,000 rows of information, instead of the newer XLSX. That’s not really a problem; the problem is that Excel doesn’t give you adequate warning when it’s discarding data, or changing it in an attempt to be helpful. And the results can be serious.

To quote the article:

Two economists, Thiemo Fetzer and Thomas Graeber … decided that no catastrophe should be allowed to occur without trying to learn some lessons. They combed through the evidence from Public Health England’s mishap. And by comparing the experiences of different regions, they concluded that the error had led to 125,000 additional infections.

…

Fetzer and Graeber have calculated a conservative estimate of the number of people who died, unknown victims of the spreadsheet error. They think the death toll is at least 1,500 people.

Think about that, as you click ‘Save As…’ and pick your data format.

(Thanks to my sister-in-law Lindsey for the link to the Harford article, which also traces some of the origins of spreadsheets from the 14th century; that’s before even I was using them!)

It always seemed probable to me that Covid infection rates would be closely related to population density. When you walk down the street, how many people do you pass? Are you in a house surrounded by fields or in a tall vertical apartment block where you share an entrance and staircase with many other households? How big are the schools? And so on.

At a country level, though, this is difficult to test. I plotted the very latest total number of Covid-related deaths per million population against the population density per sq. km. for some countries similar to my own (UK), and it didn’t show a clear correlation.

Sources: Statista and Wikipedia.

(As usual, whatever they’re doing in the Netherlands is good. Why do the Netherlands keep doing that with everything? Please stop. It’s very annoying to the rest of us.)

Depending on your political persuasions, or whether you’re a glass-half-full or a glass-half-empty kind of person, you could interpret this in various ways!

My own view (at present), for what it’s worth, is that our government and senior civil servants didn’t put enough emphasis on lockdowns in the early months, and that cost us a lot. But they did put much more energy and resources than most other countries into securing vaccines on a huge scale, very early, and we’re now reaping the benefits. So depending on the time period you examine over the last year, the picture relative to other countries can look very different. (The sadly-missed Hans Rosling would have had some nice animations, no doubt!)

At present, if you take the long view of total Covid deaths per capita, we’re a bit higher than the average for similar countries, but our rate of new deaths is lower than almost anyone’s, so we will probably look better over time. So it could have been much better, and it also could have been much worse.

Anyway, back to population density. The problem is that density is far from evenly distributed. If I plot England on the map, as distinct from the UK as a whole, it appears in a very different place: the top-right:

England is up there with the most-afflicted other countries from my list — Italy and Belgium — but it does have a notably higher population density than any of them.

Anyway, the results of my quick graphs are that I was probably wrong: it’s not clear that population density is a useful metric, at least when done at this scale.

What we really need, if we want to compare the situation in different countries, I think, is statistics about both Covid cases and population density across Europe on a 20km grid. Then we could compare them more usefully, and one day, perhaps, we’ll know whether I’m wrong in the details too, or only on the larger scale!

Yesterday, in response to another thread about the AstraZeneca vaccine concerns, I tweeted,

“I hear there’s also a risk of having a car accident while driving to or from your AZ vaccination! Why is this not being revealed to the public?”

Which got some cheery replies, like,

“You could be run over walking from your car too, these car parks are dangerous places!”

And Clive Brown responded with a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation which showed that, yes, indeed, if you drove 6 miles for your vaccine, an accident was more likely than a blood clot.

Getting mine tomorrow, if I survive the journey…

In the next few months, most of us will start to face a whole range of new social situations for which even the most careful perusal of Debrett’s will have left us unprepared.

No doubt you’ve already already pondered how best to communicate some of the following ideas (or respond when others say them to you), so please write in with your suggestions. Our agony aunt will be addressing these and other social dilemmas in a future column.

Topics for discussion:

“I have a mask here, and am very happy to put it on if you are at all uncomfortable with the distance between us. Ah, you have one too? Let’s see who feels the need to put it on first.”

“We’d like to invite you for dinner, but are unsure how soon you will feel comfortable with this. Could you suggest some months that would work for you?”

“‘Dress: black tie and mask. Decorations may be worn.’ Would wearing a mask in my regimental colours be appropriate?”

“Your story is very interesting and you’re clearly very excited about it. Would you mind standing downwind of me while you tell it?”

“That’s a very kind invitation, but I happen to know your husband is an anti-vaxxer and I’m not coming near your den of contagion until the R number is below 0.2.”

“Mr and Mrs Wyndham-Smythe request the pleasure of your company at the wedding of their daughter Sophie, as long as not more than 14 other people accept the invitation.”

“I find you very attractive and I’m not currently socially interacting with anybody else at the moment. I don’t wish to be too forward but… would you like to be in my bubble?”

In my post yesterday, I forgot to mention the final twist to my open-air Teams meeting, which made it even more surreal.

Just after pressing the ‘Leave meeting’ button on the app, I walked through our village churchyard and fell into conversation with a gravedigger. No, really. He was filling in a hole, and, leaning on his spade, told me that the heavy clay around here was nothing compared that that around Lavenham. It was a strangely Shakespearian encounter; I half-expected him to bend down, pick up a skull and ask if I recognised it.

After a brief but cheery discussion, I bade him good day and departed, thinking that I should probably have tossed him half a crown for good luck, or something.

Definitely not my typical office meeting, I thought to myself, and Tilly and I walked home debating the whims of Lady Fortune in iambic pentameter.

Every Wednesday afternoon during term, we have a departmental meeting for the senior staff, which used to take place in an efficient but not-very-inspiring and rather windowless room in the Lab. There are typically 50-100 attendees, and so, when it moved into the virtual world, we don’t in general use video; most people only turn on their cameras when they’re talking.

Well, this week, a rather wonderful thought occurred to me.

Since this meeting is essentially an audio-only experience, I realised I didn’t need to postpone my dog-walk until after it had finished. Why not do them at the same time? Especially since I was more likely to be in the role of audience than presenter for the duration of this one. Much more efficient.

So I fired up Microsoft Teams on my phone, put it in my jacket breast pocket where I knew the speaker would be clearly audible (since that’s how I normally listen to podcasts and audiobooks), and headed out.

Now, it’s rare for me to say anything good about Teams — actually, it’s rare for anyone to say anything good about Teams, as far as I can see — but on this occasion it performed beautifully, the audio quality was excellent and the video, when people did turn on their cameras, was excellent too, albeit slightly blurred by the raindrops.

At the end of the meeting, as people were saying goodbye, I turned on my camera to reveal that I was in fact wrapped up and squelching through the mud in pursuit of my spaniel, something nobody had been aware of up to that point. And for me, it had been a thoroughly enjoyable meeting. Just imagine what it would be like in sunshine!

Anyway, strongly recommended, if you have the option. Combine your meetings with your daily exercise. Go and watch the rabbits. I promise you it’ll be a more pleasant experience than sitting in your average office meeting room.

And remember, there’s no such thing as bad weather, only inappropriate clothing.

I’m a middle-aged computer geek, but my iPhone is too old to run the NHS Track & Trace app. I think this is a limitation of the Bluetooth hardware, but my phone also can’t run a recent-enough version of the operating system.

This isn’t a criticism of the app; you need the right hardware to do something like this. But it makes me wonder about the proportion of the population that will actually be able to run it. Perhaps middle-aged computer geeks like me are actually the most likely to have elderly phones? I wonder whether anyone has done a graphic, plotting the age of users against the age of their smartphones? Probably a kind of 3D histogram?

On the one hand, younger users are probably more likely to be swayed by a desire for the latest gadget and by competition with their peers. But older users are, I guess, more likely to have the disposable income to upgrade. Mmm.

And now, of course, we have some interesting extra dimensions. The effectiveness of the app is highly dependent on its market penetration, and that penetration in different age-groups is going to be constrained by this distribution.

Is it particularly important that older people, who are more vulnerable to Covid, have this app? Well, probably not directly, because the app doesn’t protect you; it protects those who may come into contact with you in the future. On the other hand, perhaps older people are more likely to be in contact with other older people in the future, so it is important that they know when they shouldn’t be socialising.

There are lots of lovely opportunities for research, here, and for inventive data visualisation. Anyone got any funding available?

One thing is clear, though. The more of a social animal you are, of whatever age group, the more important it is that you run this. (That’s a serious point, so no snarky comments, please, about whether middle-aged computer geeks often fall into that category.)

Now, here’s a last thought. I have been considering that it may finally be approaching the time when I do upgrade my phone. But I’m likely to wait until Apple announces their next models, presumably sometime between now and Christmas. (This isn’t because I want the latest one, necessarily, but because the current top model will probably be demoted to a cheaper price bracket when its position is usurped.) I imagine many others may be in the same position, and large numbers of us will become track-and-traceable only after that point.

So…

Given that this same technology is being used around the world, how many lives might be dependent on the timing of the next Apple and Samsung product announcements?

Most of us are pretty familiar with standard Zoom calls by now, but if you’re asked to organise one with more than a couple of dozen participants, you may wish to make use of Zoom’s ‘Webinar mode‘, where you have a limited number of presenters (or ‘panelists’) and the majority of participants are just ‘attendees’. Attendees are able to watch, listen, and type questions, but are not normally visible or audible themselves, unless you promote them to be panelists too (which you can do on the fly).

Webinar mode is a paid add-on, but if you have a basic paid Zoom plan, you can add it on a monthly basis when you need it. It gives you some extra options like an Eventbrite-style registration system, polls, Q&A chat windows, post-call surveys, the ability to livestream to YouTube, etc. You can find out the details on Zoom’s site. Overall, while there are a few things I would like to change, it works really quite well.

But it is a bit different from a normal Zoom call, and having run a few of these now, ranging from tens to hundreds of attendees, I’ve come up with some tips and a checklist I run through beforehand, and I thought others might find them useful.

This may all look like a daunting amount of preparation, but it needn’t take too long, and going through it can remove a much more daunting amount of stress! If any of these steps does take a significant amount of time, then it’s certainly something you want to find out before, rather than during, your webinar!

There are lots of general video-conferencing basic tips you can find out there on the web, of course. Things like:

I won’t go into any more of these because I assume we all know them by now, but make sure your panelists do, too. In fact, if there’s just one tip you should take away, it’s this:

The trial session should include you, any speakers, and one or two other helpers. You want everyone to know what it’s like to be a panelist, and what it’s like to be an attendee. Things you’ll want to find out:

You need more than just two of you to try this kind of thing out.

You’ll also want to check all of the basic things listed in the previous section for each speaker, of course, and consider whether anything is likely to change. Are they in the same venue, on the same network, using the same machine, and will the lighting be different at the time of the actual webinar?

However, don’t hold your trial session just before the event! You may need to tell your keynote speaker that they’ll need to find a different location because they’re just a silhouette. Or they must borrow a different microphone. Or plug in an external keyboard. Or lock their children in the basement.

We were preparing for one lecture where the trial session was great. Our speaker normally worked from her conservatory/garden room, the lighting was good, and the acoustics were better than expected; everything was ready to go. And then, a couple of days beforehand, I looked at the weather forecast and realised that we were in for a major heatwave on that day! The conservatory was not going to be the right venue after all, and she had to do significant moving of furniture, lighting and equipment (followed, of course, by another trial session to check the new setup).

If your speakers are going to be sharing their screen, test that out in advance with every speaker. A couple of days ago, in a trial session, two of my panelists discovered that they hadn’t done Zoom screen-sharing on their Macs before. They needed to go into System Preferences and grant Zoom the appropriate permissions, then restart the app. You don’t want them to discover this just after you’ve introduced them to the audience.

One last point on trial sessions: when you set up a Zoom webinar, you’ll be asked if you want to enable a ‘Practice session’. This is also useful, but it is slightly different: Practice sessions allow panelists, and panelists only, to connect and check things out and chat just before the meeting starts. All the other attendees just get told that the meeting will begin soon, until you, the host, click the magic ‘Broadcast’ button, and the stage curtain rises.

So yes, you probably want to do a ‘practice session’ too, but think of it as ‘waiting in the wings’, rather than the dress rehearsal. It isn’t the right time for experimenting with what attendees can or can’t see or do, nor is it the time for discovering potential issues that may take longer to fix. That’s why I picked a different name for a ‘trial session’ above: don’t rely just on the practice session unless you and all the presenters have done this together on a regular basis. Set up a separate webinar for your trial, and make sure you use the same settings for the real event. Make sure, too, that your panelists are quite clear about which meeting link is which!

We’ve also learned:

Some of these involve Zoom settings that you can set up beforehand, others can be changed on the fly or during the meeting. In the case of the former, you may need to use the Zoom web interface to make the change; you can’t do everything through the app.

In advance, or at the start while people are taking their seats:

Tell the panel:

When the meeting starts, tell the attendees:

During the webinar:

You may want to ‘Spotlight’ a speaker’s video. Normally, Zoom will show the video stream of the current speaker. (Viewers can override this at their end by ‘pinning’ a certain view.) If your webinar is a panel session, you want this auto-switching. If it’s a single speaker, then you should also be fine, because everybody else will be muted, so it won’t switch anyway. However, ‘spotlighting’ the speaker’s video is a good safety measure to stop unexpected switches when somebody’s dog barks in the background after you forgot to mute them!

If, at the conclusion, you have questions or discussions involving other panelists, you probably want to switch off spotlighting at that point, so that the other speakers are visible again, and questions don’t come as disembodied voices from the ether.

And finally:

Right, there are many more things I could cover, but I hope that highlights a few things that you might want to consider, especially if you haven’t done this webinar thing before! Have fun, and I hope it goes well!

Yesterday, we took the day off and went to the North Norfolk coast. Maintaining social distancing wasn’t too hard. And Tilly got lots of exercise.

That old pipeline that runs out along across one of our favourite beaches has clearly seen some action in the past:

Rose said this looks like two friends embracing across a fence:

And at times, sections of the pipe emerge like a sea monster from the deep:

Here you might be walking on fresh samphire…

or crunching on cockle shells.

It was great to return to a place we’ve visited often and always enjoy.

(I posted a rather different photo from here on a previous visit.)

Now, you may well be asking, how did you manage this, when almost everything is closed? This particular beach is about an hour and three-quarters’ drive from Cambridge, and that poses some challenges when it comes to… ahem… the need for a comfort break.

Well, the answer is that we’re fortunate enough to have a small campervan.

We can’t use it for any overnight stays at present, but it does make a jolly good vehicle for day trips. It has a fridge, a table, a stove, fresh water…

And it also has a loo. Sort of. Even in a van this size. Now, we don’t often use the loo, because we usually stay on sites that have such facilities, and, well, frankly, a loo that you have to pull out of a cupboard before use isn’t that much of a ‘convenience’. Sometimes we leave it behind, because the cupboard space is more useful, and when we have used it in the past, it generally goes in a little loo tent we pitch beside the van.

Having said, that, these facilities have come a long way since the more primitive equivalents I remember from my youth. Ours is Thetford Excellence, in case you’re interested, and it’s remarkably civilised. All the necessary seals are good, modern chemicals do a good job, it incorporates a loo roll holder and even, would you believe, an electric flush! There are some places I never expected to install AA batteries… but it works well. We probably wouldn’t have chosen quite such a luxurious one, but it came with the van.

Anyway, the point is that this does, pretty much single-handedly, enable day trips during lockdown. “Would you like to take the dog for a short walk, dear? I’m just going to draw the curtains…”

Anyway, back to the beaches. The Norfolk beaches we visit are never crowded, but the car parks can be, so we made sure we arrived early. By the time we departed, a couple of hours later, somebody was grateful for our space.

We had lunch in a different car park, at Blakeney. There was still plenty of space here.

We managed to get a takeaway coffee and cake from a favourite spot in Holt which does an awfully good job of both, and then headed for a rather different beach at Weybourne in the afternoon.

Here, you’re walking on pebbles, which is not quite so easy, but they’re beautiful none the less.

We always bring some of the more colourful pebbles or shells back from our seaside trips, and they end up decorating the bird-bath in the garden.

Talking of birds, there were lots of happy ones bobbing about.

And there are suitably picturesque scenes to be snapped even from the car park.

The standard way to get one of these boats over a pebbly beach into the sea, by the way, is to attach a small accessory.

It’s basically a big chunk of ferric oxide with a diesel engine.

Anyway, all in all, a very pleasant day, and, being aware of the hardship many others are going through at present, I was enormously lucky to be able to enjoy it in such a versatile vehicle with my two favourite companions.

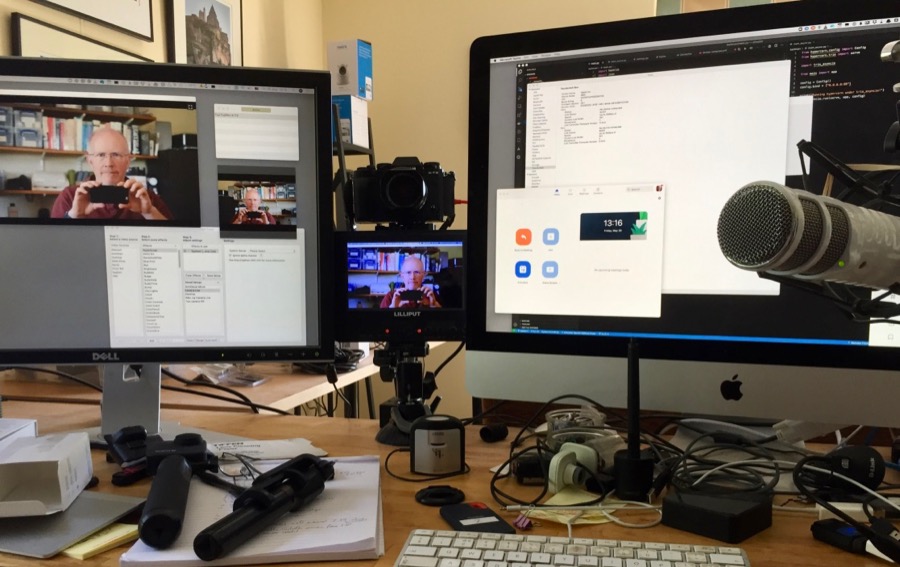

Yesterday I realised I was looking particularly suave and debonair, so decided it would be the right time to point a camera at myself. Mmm…

If you want to try using a decent digital camera for videoconferencing, you normally either need:

something which will capture an HDMI output signal from your camera and feed it into your computer over USB, like the Elgato Cam Link,

or you need some software which can capture the live preview output and make it available to your operating system as if it were a locally-connected camera. On the Mac, I do this with a combination of Camera Live – which makes it avaliable as a ‘Syphon’ server – and CamTwist, which can take a variety of inputs, including Syphon, and blend them into a ‘virtual camera’ output. There are various tutorials online on how to do this. OBS is a similar popular app, but doesn’t yet support virtual camera output on the Mac.

Finally, for some versions of some Mac apps, you may need to remove the app’s signature (which identifies it with a certain set of permissions), to enable it to see virtual cameras as well as physical ones. At the time of writing, Zoom needs:

$ codesign --remove-signature /Applications/zoom.us.app/

P.S. Sadly, various other people have used the phrase ‘One man and his vlog’, so I can’t pinch it on any kind of long-term basis 🙂

© Copyright Quentin Stafford-Fraser

Recent Comments