Esther Bintliff has a splendid (longish) piece in the FT entitled, “Feedback required: the science of criticism that actually works“. She begins:

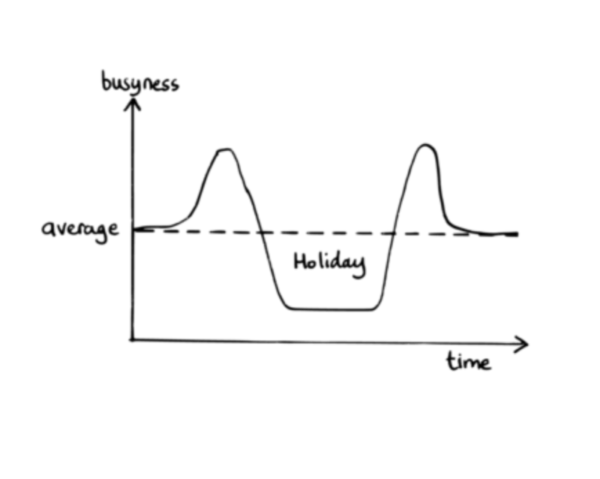

Years ago, after I received some negative feedback at work, my husband Laurence told me something that stuck with me: when we receive criticism, we go through three stages. The first, he said, with apologies for the language, is, “”Fuck you.”” The second is “”I suck.”” And the third is “”Let’s make it better.”” I recognised immediately that this is true, and that I was stuck at stage two.

These three stages seem to be somewhat universal, and many people, she points out, never even make it as far as stage two, and get hung up at the angry response. But you can only benefit from feedback if you get through both of those stages to the third.

Depending on your personality, you may be more likely to stay at stage one, confident in your excellence and cursing the idiocy of your critics. The problem, Laurence continued, is being unable to move on to stage three, the only productive stage.

Now, this is simple, memorable, and worthy of regular contemplation, and the article would have been useful if it stopped there. But no, there’s plenty more good stuff to come.

How, for example, should you ask for feedback if you actually want people to give it to you?

How might your feedback be presented in a way that helps others to get to stage three?

How is this connected to The West Wing?

And how often is any sort of feedback actually worthwhile? What about those regular performance reviews that so many businesses undertake? She talks about when Avraham Kluger met Angelo DeNisi, both researchers in this area..

When Kluger told him he was studying the destructive effects of feedback on performance, DeNisi was intrigued. “”My career is based on performance appraisal and finding ways to make it more accurate. You’re telling me the assumptions are incorrect?”” he asked. “”Yes, I’m afraid I am,”” replied Kluger.

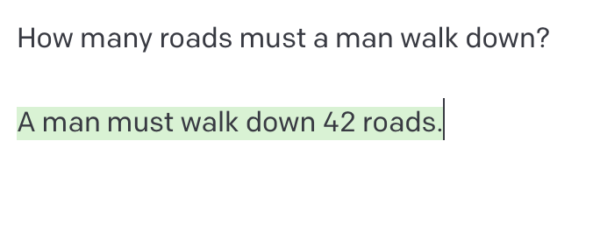

The two reviewed hundreds of feedback experiments going back to 1905. What they found was explosive. In 38 per cent of cases, feedback not only did not improve performance, it actively made it worse. Even positive feedback could backfire. “”This was heresy,”” DeNisi recalls.

I think this is another example of very enjoyable and informative journalism from the FT, but it is behind their paywall, so I shouldn’t reproduce too much of it here.

Too financial for our times?

The problem with the FT is that it is really quite expensive as online publications go. £1 or so per day does add up over the year, and makes it more expensive, for example, than Netflix, Spotify and Disney+ combined. Bizarrely, you can have them deliver a paper version through your door each day for somewhat less than even their basic digital access package.

If, however, you are rather wealthy, or, like me, you’re fortunate enough to be associated with an organisation that pays for FT access, then I would suggest it’s a perk well-worth exploring. (The iPad app is also good, and lives on my home screen.)

If not, I guess you can keep an eye on the headlines and pop to the newsagent if you see something that piques your interest. Remember newsagents? I guess they’re not just for cans of San Pellegrino — they’re a useful alternative to bits of the internet that are too expensive.

In the meantime, I have a small number of gift links I can use to give non-subscribers access to the article, so get in touch if you’d really like to read the rest of it.

There! That should get me some nice feedback.

Recent Comments