Google Street View is, I think, one of the most amazing achievements in recent times, and it’s one of the things that keeps me using Google Maps even though many of the alternatives are rather good. If I’m heading to a new destination, I’ll often look in advance at, say, the entrance gate, or the correct exit from the last roundabout, so those final manoeuvres when the traffic is slowing down behind you are less stressful: you’re in familiar surroundings. Street View is, in that sense, a déjà-vu-generator.

And of course, it’s great for bringing back memories of places * qu’on a vraiment déjà vu*. We can all think of dozens of examples; for me, this morning, the sea front by the Ullapool ferry terminal is somewhere I remember as a launching point into the unknown; it’s where I stayed at a lovely inn before catching the ferry to the Outer Hebrides. Happy memories.

But there are interesting questions to be asked about Street View as well. For someone who enjoys window-shopping on Rightmove for a possible next home, it’s a very valuable tool, and I’ve often wondered how much the market appeal of your property is affected by whether the Google car drove by on a sunny or a cloudy day!

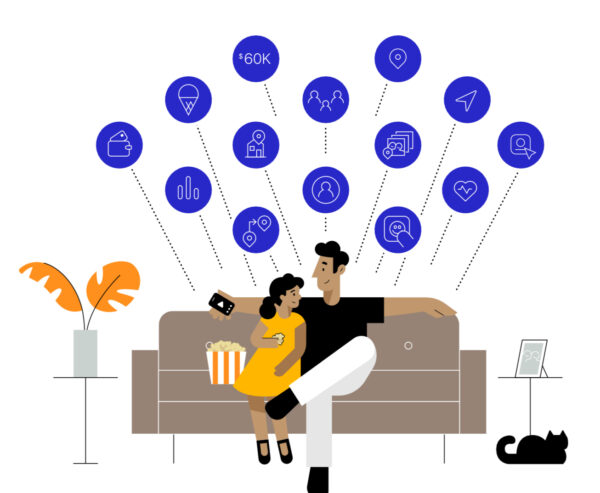

And this morning, I saw debates on Twitter about research that used images of your house on Street View to estimate how likely you were to have a car accident, something which could be used against you by insurance companies (or, of course, in your favour, but that doesn’t make such good headlines).

The paper’s here, and I was most surprised by just how poor the insurance company’s existing model was; information about your age, gender, postcode etc apparently doesn’t give them as much insight as you might expect, and knowing whether you live in a well-maintained detached house in a nice neighbourhood gives them just a little bit more. Some see this as very sinister, but you need to remember that this wasn’t some automated image-analysis system; the researchers had to spend a lot of time looking at StreetView pictures of houses and annotating them by hand with their assessment of the condition, type of house, etc. Some of this could be performed by machines in future, but there are lots of other factors to consider as well: is the issue that you are more likely to crash into somebody in certain neighbourhoods, or that they are more likely to crash into you? What’s the speed limit on the surrounding streets? How close is the pub? And so on…

So I sat down thinking I would write about this, but one thing I failed to notice was the date of the research. I assumed that because people were talking about it on Twitter today, it must be new — a fatal mistake. What’s more, just a little bit of further research showed me that my friend John Naughton had written a good piece about it in the Observer two years ago.

So it’s perhaps not surprising that I like technologies that can give me a sense of déja vu. My own abilities in that area are clearly lacking!

It was a more down-to-earth recommendation that led me to start writing this post, however! We bought ourselves a Christmas present of the complete Miss Marple, and, even though we’ve seen them all before at some point, we often can’t remember whoactuallydunnit. It has proved to be a very good purchase, and we can comfortably recommend that before bed — whatever you may have had to endure in the day’s news, Zoom calls, or tweets — heading to St Mary Mead with Joan Hickson is a very pleasant way to finish the day.

It was a more down-to-earth recommendation that led me to start writing this post, however! We bought ourselves a Christmas present of the complete Miss Marple, and, even though we’ve seen them all before at some point, we often can’t remember whoactuallydunnit. It has proved to be a very good purchase, and we can comfortably recommend that before bed — whatever you may have had to endure in the day’s news, Zoom calls, or tweets — heading to St Mary Mead with Joan Hickson is a very pleasant way to finish the day.

Recent Comments