This is a very geeky post for those who might be Googling for particular details of Linux containerisation technologies. Others please feel free ignore! We were searching for this information online today and couldn’t find it, so I thought I’d post it myself for the benefit of future travellers…

How happy are your containers?

In your Dockerfile, you can specify a HEALTHCHECK: a command that will be run periodically within the container to ascertain whether it seems to be basically happy.

A typical example for a container running a web server might try and retrieve the front page with curl, and exit with an error code if that fails. Something like this, perhaps:

HEALTHCHECK CMD /usr/bin/curl --fail http://localhost/ || exit 1

This will be called periodically by the Docker engine — every 30 seconds, by default — and if you look at your running containers, you can see whether the healthcheck is passing in the ‘STATUS’ field:

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE CREATED STATUS NAMES

c9098f4d1933 website:latest 34 minutes ago Up 33 minutes (healthy) website_1

Now, you can configure this healthcheck in various ways and examine its state through the command line and other Docker utilities and APIs, but I had always thought that it wasn’t actually used for anything by Docker. But I was wrong.

If you are using Docker Swarm (which, in my opinion, not enough people do), then the swarm ensures that an instance of your container keeps running in order to provide your ‘service’. Or it may run several instances, if you’ve told the swarm to create more than one replica. If a container dies, it will be restarted, to ensure that the required number of replicas exist.

But a container doesn’t have to die in order to undergo this reincarnation. If it has a healthcheck and the healthcheck fails repeatedly, a container will be killed off and restarted by the swarm. This is a good thing, and just how it ought to work. But it’s remarkably hard to find any documentation which specifies this, and you can find disagreement on the web as to whether this actually happens, partly, I expect, because it doesn’t happen if you’re just running docker-compose.

But my colleague Nicholas and I saw some of our containers dying unexpectedly, wondered if this might be the issue, and decided to test it, as follows…

First, we needed a minimal container where we could easily change the healthcheck status. Here’s our Dockerfile:

FROM bash

RUN echo hi > /tmp/t

HEALTHCHECK CMD test -f /tmp/t

CMD bash -c "sleep 5h"

and we built our container with

docker build -t swarmtest .

When you start up this exciting container, it just goes to sleep for five hours. But it contains a little file called /tmp/t, and as long as that file exists, the healthcheck will be happy. If you then use docker exec to go into the running container and delete that file, its state will eventually change to unhealthy.

If you’re trying this, you need to be a little bit patient. By default, the check runs every 30 seconds, starting 30s after the container is launched. Then you go in and delete the file, and after the healthcheck has failed three times, it will be marked as unhealthy. If you don’t want to wait that long, there are some extra options you can add to the HEALTHCHECK line to speed things up.

OK, so let’s create a docker-compose.yml file to make use of this. It’s about as small as you can get:

version: '3.8'

services:

swarmtest:

image: swarmtest

You can run this using docker-compose (or, now, without the hyphen):

docker compose up

or as a swarm stack using:

docker stack deploy -c docker-compose.yml swarmtest

(You don’t need some big infrastructure to use Docker Swarm; that’s one of its joys. It can manage large numbers of machines, but if you’re using Docker Desktop, for example, you can just run docker swarm init to enable Swarm on your local laptop.)

In either case, you can then use docker ps to find the container’s ID and start the healthcheck failing with

docker exec CONTAINER_ID rm /tmp/t

And so here’s a key difference between running something under docker compose and running it with docker stack deploy. With the former, after a couple of minutes, you’ll see the container change to ‘(unhealthy)’, but it will continue to run. The healthcheck is mostly just an extra bit of decoration; possibly useful, but it can be ignored.

With Docker Swarm, however, you’ll see the container marked as unhealthy, and shortly afterwards it will be killed off and restarted. So, yes, healthchecks are important if you’re running Docker Swarm, and if your container has been built to include one and, for some reason you don’t want to use it, you need to disable it explicitly in the YAML file if you don’t want your containers to be restarted every couple of minutes.

Finally, if you have a service that takes a long time to start up (perhaps because it’s doing a data migration), you may want to configure the ‘start period’ of the healthcheck, so that it stays in ‘starting’ mode for longer and doesn’t drop into ‘unhealthy’, where it might be killed off before finishing.

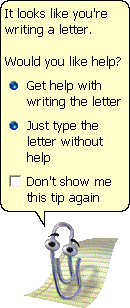

And so for some of us, the trick became learning how to turn off and hide as many of these features as possible, partly to avoid confusing and overwhelming users, and partly just to get on with the actual business of creating content, for which we were supposed to be using the machines in the first place. One feature which became the iconic symbol of unwanted bloatware was ‘Clippy’ (officially the

And so for some of us, the trick became learning how to turn off and hide as many of these features as possible, partly to avoid confusing and overwhelming users, and partly just to get on with the actual business of creating content, for which we were supposed to be using the machines in the first place. One feature which became the iconic symbol of unwanted bloatware was ‘Clippy’ (officially the

Back in about 1993, I was doing the bookkeeping for a big project being undertaken by my local church. Donations were flooding in, and we needed to keep track of everything, send out receipts, forms and letters of thanks, and note whether each donation was eligible for the UK tax relief known as ‘Gift Aid’.

Back in about 1993, I was doing the bookkeeping for a big project being undertaken by my local church. Donations were flooding in, and we needed to keep track of everything, send out receipts, forms and letters of thanks, and note whether each donation was eligible for the UK tax relief known as ‘Gift Aid’.

Recent Comments